2020-2021 Annual Report

Table of contents

- Message from the Commissioner

- 2020–21 in review

Upholding the right of access during the pandemic - The OIC’s impact on the access regime

Investigating and reporting on complaints - Observations on the state of the access regime

- Adapting to a new reality

Maintaining our operations - Focusing on the future

- About the Office of the Information Commissioner

- Appendix – Annual report of the Information Commissioner Ad Hoc

Message from the Commissioner

This report highlights the work and dedication of the employees of the Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) during the 12-month period of April 2020 to March 2021, summarizes the OIC’s efforts to ensure that Canadians’ right of access is fully respected and shares some observations regarding the state of the access to information regime.

The past year has brought significant changes to the way the OIC conducts investigations and carries out the other work that supports my mandate. The way my team adapted to these transformations demonstrated the resilience of the OIC’s workforce and the high calibre of the people who work in my office.

The pandemic forced the OIC to greatly expand the use of technology, ensuring health and safety measures were in place for those who were required to physically go to the office, and sharing information with employees to help them manage their health and safety at home and maintain their physical and mental health. Most importantly, it meant finding ways to continue to carry out the investigations that are at the core of our mandate in an environment where access to our physical premises was significantly curtailed for significant stretches of time. We were able to meet the objectives we had set for ourselves, while also concluding several systemic investigations that have become a catalyst for change within institutions.

The year also brought welcome financial news: in August 2020, an OIC request that temporary funding it had received for four years be made permanent was approved by the Treasury Board of Canada. This ongoing funding in the amount of $3 million has been allocated to the OIC to ensure it can continue to effectively play its oversight function. Thanks to this permanent funding, the OIC will be able to maximize the effectiveness of its resources and the results it can achieve for Canadians.

In addition, through my submission to the review of the access to information regime, I highlighted a number of areas requiring leadership on the part of the government, including investing in human resources as well as technological innovation. I continue to stress, as I have for months, that there is an immediate need for concrete action, independent of the review process, to address the critical state of the system that changes to the Access to Information Act (the Act) alone cannot fix. As I stated in the early days of the pandemic, I believe that it is only by being fully transparent, and respecting good information management practices and the right of access, that the government can build an open and complete public record of decisions and actions taken during this extraordinary period in our history—one that will inform future public policy decisions. Without these actions, the government’s capacity to respond to access requests and provide the information that Canadians are seeking will continue to be restricted, putting at risk the quasi constitutional right of access to information.

Caroline Maynard

Information Commissioner of Canada

2020–2021 in review

Upholding the right of access during the pandemic

April 2020

The OIC transitions to operating in a virtual environment

As 2020–21 begins, all OIC employees are working remotely and the investigations are running at 100 percent capacity.

Agile decision-making to guide operations

Under the auspices of the OIC’s Business Continuity Plan (BCP), an internal committee meets twice a week with the Commissioner and deputy commissioners to share information, respond to strategic direction, implement operational decisions and report to central agencies on COVID-19 measures and the status of operations.

Access to information in extraordinary times

The Commissioner makes a landmark statement on the importance of the right of access and the need for institutions to properly capture and store government records during times of crisis.

A critical phase for the access to information system

The Commissioner communicates her concerns to the President of the Treasury Board as many signs point to the possible collapse of a system that has been under stress for some time.

May 2020

Full steam ahead

Employees work efficiently from home, completing over 500 investigations since the beginning of the pandemic. The OIC expands its workforce as new team members are hired and trained in a completely virtual environment.

Planning for the return to the workplace

With operations running smoothly, the OIC’s BCP Committee turns its attention to planning for the eventual return to the workplace. The group creates a roadmap to follow, with clear phases and requirements.

June 2020

Speaking to Parliament: early observations on the state of access to information during the pandemic

The Commissioner appears before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates to discuss accountability and access to information.

A call for greater openness

The Commissioner calls for greater openness and transparency during a Podcast on Maclean’s Live.

July 2020

Immediate action required to repair federal access system

The Commissioner reiterates the need for strong leadership and concrete actions by the government—beyond its review of the access system—to address both long-standing problems and issues that have arisen during the pandemic.

Access at issue: Nine recommendations for National Defence

In her first special report to Parliament, the Commissioner reports on her systemic investigation into the procedures, policies and systems at National Defence for processing access requests. Media coverage of the report affords the Commissioner opportunities to emphasize the need for the federal government to be more open and transparent.

August 2020

Permanent funding: A new era for the OIC

Temporary funding the OIC had received for four years for investigation is made permanent to ensure the stability and viability of the investigations program in support of the Commissioner’s mandate. The Commissioner welcomes these resources while noting that additional funding is also required for units responsible for access requests across government institutions in order to truly effect change.

September 2020

Access sheds light on government decisions around the world

The Commissioner joins with the global access to information community during Right to Know Week to remind political leaders that access plays a vital role during times of crisis, allowing citizens to shine a light on government decision-making.

Planning for beyond 2020

The OIC begins to look beyond the pandemic, planning for post-pandemic operations, gathering lessons learned from the first six months of staff working home, and exploring ways to optimize its physical office space while creating a vision for how the organization will carry out its work in the future.

October 2020

Investigations regarding the Privy Council Office

In October and November 2020, four investigations reveal that the Privy Council Office closed access requests without processing them completely because it did not receive recommendations from other government institutions, counter to the requirements and spirit of the Act.

November 2020

Access at issue: The need for leadership

In a special report to Parliament, the Commissioner details the results of her investigation into systemic issues affecting the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)’s handling of access to information requests. The report, which gains national media attention, leads to concrete actions from the RCMP. The Commissioner discusses it on CPAC.

December 2020

Notable investigation: The pandemic does not suspend Canadians’ right of access

The Commissioner reports on a complaint she launched against Canadian Heritage based on reports it had stopped processing access requests during the pandemic.

(Virtually) connecting with institutions

Throughout the year, the OIC participates in a number of meetings with institutions. These activities range from speaking to a group of public servants during the Right to Know Week to all-staff meetings of access to information and privacy (ATIP) employees. The OIC also takes part in a Library of Parliament Seminar to explain the Commissioner’s role and priorities.

January 2021

The government’s access system review: The Commissioner weighs in

The Commissioner submits her observations to the President of the Treasury Board, which include a myriad of ways to improve the access regime and many that do not require legislative changes. Measures that fall under this category can and should be implemented immediately.

February 2021

Updating parliamentarians on the state of access during the pandemic

The Commissioner makes a return appearance before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates as part of its study of the government’s pandemic response.

March 2021

Emphasizing the need for leadership from the top

The Commissioner begins meeting ministers whose portfolios include institutions subject to the most access-related complaints. She urges ministers to take on a greater role in upholding the right of access, stressing the importance of the necessary resources, processes and tools being in place so institutions can meet their obligations under the Act. She also offers insights into how institutions can improve their performance in the area of access.

The OIC’s impact on the access regime

Investigating and reporting on complaints

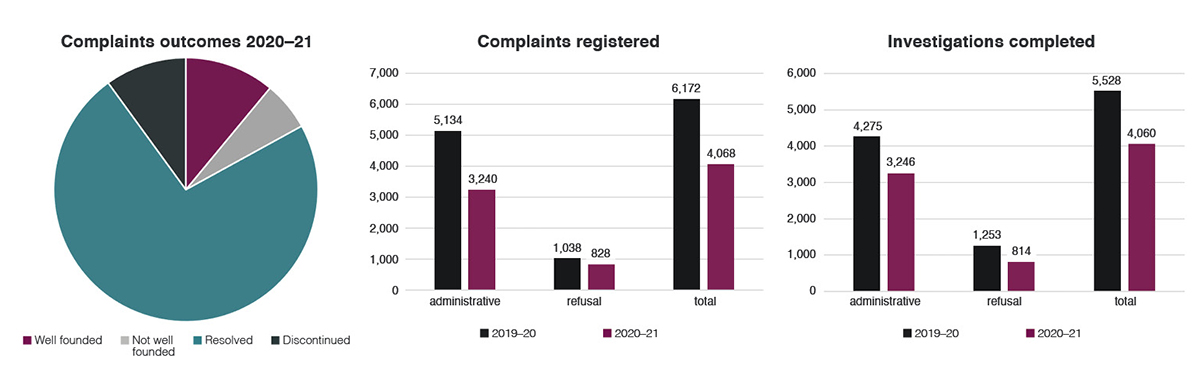

Throughout 2020–2021, the OIC has continued to deliver on its mandate to conduct investigations. Despite the challenges associated with the pandemic, the OIC set a goal of completing 4,000 files in 2020–2021. Thanks to the resilience, hard work and commitment of its employees, in collaboration with institutions, the OIC achieved this goal, completing 4,060 complaints by March 31, 2021.

The OIC also led investigations on four Commissioner-initiated complaints, including three systemic investigations. In addition, the OIC recorded 34 percent fewer complaints in 2020–2021. This drop could be attributed to the pandemic and the fact that institutions seem to have received fewer access requests over the past year according to data compiled to date.

| OUTCOMES | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well founded | 597 | 11% | 643 | 16% |

| Not well founded | 344 | 6% | 225 | 5% |

| Resolved | 4,057 | 73% | 2,867 | 71% |

| Discontinued | 530 | 10% | 325 | 8% |

| TOTAL | 5,528 | 100% | 4,060 | 100% |

Since June 2019, the Access to Information Act gives the Information Commissioner the authority to publish reports of her findings. The final reports of some of the key investigations the OIC has completed in 2020-2021 provide guidance to institutions and complainants by establishing the Commissioner’s position on various sections of the Act. In 2020–2021, the OIC also published guidance for complainants and institutions, while augmenting its suite of internal resources for investigators.

Text version

Complaints outcomes for 2020–2021

| Well founded | 16% |

| Not well founded | 5% |

| Resolved | 71% |

| Discontinued | 8% |

Complaints registered in 2019-2020 and 2020–2021

| Complaints registered | 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative complaints | 5,134 | 3,240 |

| Refusal complaints | 1,038 | 828 |

| Total of complaints registered | 6,172 | 4,068 |

Investigations completed in 2019-2020 and 2020–2021

| Investigations completed | 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative complaints | 4,275 | 3,246 |

| Refusal complaints | 1,253 | 814 |

| Total of complaints registered | 5,528 | 4,060 |

Complaint Activity in 2020–2021

Complaints

as of April 1, 2020

New complaints

registered in 2020-2021

Investigations

completed in 2020-2021

Outcome

Well founded

Not well founded

Resolved

Discontinued

Total

| Complaints as of April 1, 2020 | New complaints registered in 2020-2021 | Investigations completed in 2020-2021 | Well founded | Not well founded | Resolved | Discontinued | Ceased | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 938 | 2,507 | 2,602 | 100 | 27 | 2,429 | 46 | 2,602 | |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 324 | 275 | 344 | 117 | 25 | 178 | 24 | 344 | |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 478 | 102 | 129 | 47 | 18 | 37 | 27 | 129 | |

| Privy Council Office | 202 | 99 | 61 | 35 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 61 | |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 147 | 137 | 102 | 35 | 13 | 37 | 17 | 102 | |

| National Defence | 219 | 61 | 106 | 69 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 106 | |

| Library and Archives Canada | 191 | 51 | 21 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 21 | |

| Global Affairs Canada | 148 | 47 | 81 | 28 | 5 | 10 | 38 | 81 | |

| Department of Justice Canada | 100 | 91 | 39 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 39 | |

| Correctional Service Canada | 53 | 92 | 48 | 18 | 1 | 21 | 8 | 48 | |

| Parks Canada | 113 | 16 | 19 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 19 | |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 51 | 69 | 35 | 11 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 35 | |

| Transport Canada | 56 | 63 | 39 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 39 | |

| Health Canada | 84 | 27 | 52 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 52 | |

| Department of Finance Canada | 75 | 26 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 23 | |

| Canadian Security Intelligence Service | 66 | 33 | 38 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 11 | 38 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 44 | 35 | 18 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 18 | |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 54 | 14 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 21 | |

| Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | 47 | 20 | 43 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 26 | 43 | |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs | 56 | 9 | 24 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 24 | |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 41 | 18 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 | |

| Public Safety Canada | 37 | 20 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 11 | |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 35 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Natural Resources Canada | 34 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 11 | |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 35 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| SubTotal | 3,628 | 3,832 | 3,886 | 599 | 187 | 2,809 | 291 | 3,886 | |

| Other Institutions | 357 | 236 | 174 | 44 | 38 | 58 | 34 | 174 | |

| Total | 3,985 | 4,068 | 4,060 | 643 | 225 | 2,867 | 325 | 4,060 |

Text version

Complaint Activity in 2021–2021

| Active complaints in 2020–2021 | Investigations completed in 2020–2021 | Outcome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active complaints as of April 1, 2020 | Complaints registered between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021 | Total | Complaints registered before April 1, 2020 | Complaints registered between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021 | Total | Well founded | Not well founded | Resolved | Discontinued | Total | |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 938 | 2,507 | 3,445 | 892 | 1,710 | 2,602 | 100 | 27 | 2,429 | 46 | 2,602 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 324 | 275 | 599 | 204 | 140 | 344 | 117 | 25 | 178 | 24 | 344 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 478 | 102 | 580 | 95 | 34 | 129 | 47 | 18 | 37 | 27 | 129 |

| Privy Council Office | 202 | 99 | 301 | 41 | 20 | 61 | 35 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 61 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 147 | 137 | 284 | 58 | 44 | 102 | 35 | 13 | 37 | 17 | 102 |

| National Defence | 219 | 61 | 280 | 95 | 11 | 106 | 69 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 106 |

| Library and Archives Canada | 191 | 51 | 242 | 20 | 1 | 21 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 21 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 148 | 47 | 195 | 75 | 6 | 81 | 28 | 5 | 10 | 38 | 81 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 100 | 91 | 191 | 33 | 6 | 39 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 39 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 53 | 92 | 145 | 28 | 20 | 48 | 18 | 1 | 21 | 8 | 48 |

| Parks Canada | 113 | 16 | 129 | 16 | 3 | 19 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 19 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 51 | 69 | 120 | 19 | 16 | 35 | 11 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 35 |

| Transport Canada | 56 | 63 | 119 | 23 | 16 | 39 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 39 |

| Health Canada | 84 | 27 | 111 | 39 | 13 | 52 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 52 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 75 | 26 | 101 | 18 | 5 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 23 |

| Canadian Security Intelligence Service | 66 | 33 | 99 | 27 | 11 | 38 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 11 | 38 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 44 | 35 | 79 | 15 | 3 | 18 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 18 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 54 | 14 | 68 | 20 | 1 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 21 |

| Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | 47 | 20 | 67 | 29 | 14 | 43 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 26 | 43 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs | 56 | 9 | 65 | 22 | 2 | 24 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 24 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 41 | 18 | 59 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Public Safety Canada | 37 | 20 | 57 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 11 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 35 | 14 | 49 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 34 | 6 | 40 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 35 | 0 | 35 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| SubTotal | 3,628 | 3,832 | 7,460 | 1,800 | 2,086 | 3,886 | 599 | 187 | 2,809 | 291 | 3,886 |

| Other Institutions | 357 | 236 | 593 | 110 | 64 | 174 | 44 | 38 | 58 | 34 | 174 |

| Total | 3,985 | 4,068 | 8,053 | 1,910 | 2,150 | 4,060 | 643 | 225 | 2,867 | 325 | 4,060 |

Among the thousands of investigations the OIC completed this year, four of them, including three systemic investigations, focussed on key issues with the following institutions:

National Defence

The systemic investigation into National Defence’s overall processing of access to information requests was instigated partially in response to serious allegations made during the pre-trial hearings of Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, along with findings that the OIC had made in an earlier investigation involving the Office of the Judge Advocate General.

In both cases, it was alleged that National Defence had inappropriately withheld information in response to a request. The concerns raised by these findings and allegations warranted immediate action and compelled the OIC to investigate further.

The Information Commissioner identified issues and shared her findings with the Minister of National Defence, who agreed that significant improvements were needed to ensure that National Defence was fully meeting its obligations under the Act.

In response to the OIC’s recommendations, National Defence has initiated changes to improve its access to information processes, including the following:

- developing and implementing a standard operating procedure that clearly established criteria to ensure the original intent of the request is met;

- developing and maintaining a reference document list explaining the programs and mandate of each branch/program area, as well as key areas of interest;

- ensuring consultations and discussions are as efficient as possible by providing program areas with a reasonable, but specific, timeframe to respond to requests and consultations, and encouraging the use of face-to-face and teleconference discussions rather than emails and letters to facilitate consultations;

- exploring technological options and paperless systems that provide secure electronic transfer of records within National Defence’s classified systems to reduce the risk of lost or damaged records and facilitate information management;

- increasing communication and training for employees to help ensure program areas fully understand their responsibilities under the Act regarding obstruction and all employees who have access to information responsibilities as a primary and/or secondary duty have mandatory work objectives to comply with the Act.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The OIC launched an investigation into systemic issues regarding the inability of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to provide timely responses to access requests. The OIC received numerous complaints indicating that the RCMP was consistently unable to meet statutory timeframes under the Act for responding to access requests.

The special report tabled in Parliament following this investigation details six issues of concern impacting the RCMP’S ability to respond to access requests in a timely manner. The report also provides 15 recommendations for tackling these issues effectively.

The RCMP reacted to the OIC’s call for leadership

So far, the investigation has resulted in the creation of a dedicated Information Technology team at the RCMP to look at technological solutions to ease the transition from using archaic records systems to becoming a paperless organization. The RCMP also created a Divisional Consultation Committee, with each division providing resources to ensure representation from all areas and regions of the organization.

Throughout the past year, the RCMP has been one of the leading government institutions in regards to responsiveness during the pandemic, based on the number of closed files and a backlog that has not grown. The RCMP is looking at ways to add resources and refine their overall processes, approval system, and digitizing and receiving information in a timelier manner. Both the RCMP Commissioner and Minister of Public Safety have reiterated their commitment to fully address the challenges that the investigation highlighted. The Information Commissioner is looking forward to the concrete results of these measures, and will continue to monitor this institution’s performance over the coming year.

Canadian Heritage

The Information Commissioner initiated a complaint against Canadian Heritage (PCH) based on reports that the institution had suspended its processing of access requests as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The investigation found that between March 16 and July 10, 2020, PCH did not meet its legal obligations related to access to information, which had not been suspended during the pandemic.

During that period, PCH’s Access to Information and Privacy Secretariat was not granted access to its work premises and was unable to access its network remotely. This created a backlog of 224 access requests.

The investigation had an impact on PCH

The Minister of Canadian Heritage assured the OIC that although “difficult choices” had to be made in the early days of the pandemic, PCH was committed to providing Canadians with access to information at all times and that measures have been put in place to ensure full compliance with the intent and spirit of the Act.

As a result of this investigation, PCH took action to meet its legal obligations and has worked towards addressing the backlog of requests stemming from its suspension of access to information operations. PCH has also posted its progress on its website.

In partnership with Shared Services Canada, PCH has also acquired a server with remote access to house all files classified at or below Protected B. The new server, along with all requisite software, allows its staff to respond to requests remotely.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

In 2020–2021, the Information Commissioner concluded a systemic investigation she had initiated into Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). The investigation looked at the processing of access to information requests to better understand and address the dramatic increase in requests IRCC received from April 1, 2017, to February 26, 2020, as well as in complaints registered by the OIC against IRCC. The OIC closed 2,601 IRCC complaints in 2020–2021, largely administrative complaints about late responses. In many instances, the OIC’s initial inquiries determined that IRCC had already responded to the access requests. Consequently, the OIC was able to quickly resolve the vast majority of the complaints.

While the investigation was completed during the 2020–2021 fiscal year, a special report on this investigation which provides recommendations to IRCC, was tabled later in May 2021. This special report highlights priorities on which the institution is invited to focus, including the need to transform the way in which it delivers information to its clients in order to decrease the need for access requests.

IRCC is working towards a better immigration client experience

A few days after the OIC completed its investigation, IRCC sent to the Information Commissioner a plan detailing its commitments, with associated timelines, to address the issues raised in the investigation. The plan also highlights other access to information initiatives undertaken by various sectors of the institution.

The Commissioner is encouraged by IRCC’s positive reaction to her recommendations.

On the litigation front

Three applications are currently before the Federal Court where the Information Commissioner is appearing on behalf of the complainants. The applications seek disclosure by Health Canada of the second and third characters of postal codes and names of cities relating to those licensed to grow and use medical marijuana as of 2017.

Health Canada disclosed only the first character of postal codes, withholding all of the second and third characters and the names of cities as personal information. In investigations of complaints about Health Canada’s responses to access requests, the Commissioner found that additional characters of postal codes and additional names of cities could be released without disclosing personal information, as it would not render individuals identifiable. Since this information is not personal information, it must be severed from any exempt material and disclosed to the complainant. The Commissioner recommended that Health Canada disclose additional characters of postal codes and additional names of cities. Health Canada refused.

The parties’ written argument and evidence will be filed with the Court in the summer of 2021. A hearing is expected to occur in the fall of 2021.

Observations on the state of the access regime

In January 2021, the Commissioner provided the President of the Treasury Board with a written submission pertaining to the review of the access to information regime launched in June 2020. The submission was in two parts, with the first outlining general observations on the state of the access regime and the second providing concrete solutions on how to improve the system without waiting for legislation changes. The submission synthesizes actions that can be taken now, to improve the system as a whole.

Over the course of the investigations conducted in 2020–2021, the OIC compiled additional observations related to vulnerabilities in Canada’s access regime. Some of these are a direct result of the pandemic. Others are long-standing issues that have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. These include the following:

- unresponsive offices of primary interest;

- deficiencies in infrastructure for processing requests; and

- units in charge of access to information under-resourced and overwhelmed with requests, resulting in delays.

The fact that government employees spent the year working remotely on a large scale, with limited access to physical files, protected information and other resources, curtailed much of the gathering of requested documents, and by extension, the ability of access to information teams to process requests and respond to complaints. The failure to adopt proper information management practices may have also resulted in some records that are of public interest never having been created in the first place, while documents not being sorted or organized properly may have led to a lack of relevant records.

The over-classification of documents created issues in certain institutions, resulting in documents being housed on secure servers and beyond the reach of employees working remotely. Had they been properly classified, these documents would have been more easily accessible.

The OIC also observed that the access to information system relies heavily on software that has not been updated for years and on bureaucratic processes that have not kept up with the times. Even before the pandemic and the widespread adoption of alternative work arrangements, chronic under-resourcing had created backlogs in responding to access requests that had grown year after year.

While there has been a slow improvement in the last year, there are still institutions where the network cannot manage the quantity of documents to be processed, forcing employees to work evenings, nights or weekends.

Another issue unique to the pandemic is how the new working arrangements for much of the public service have had an impact on documentation practices. Working remotely has necessitated the use of different tools, such as online meeting technology and instant messaging. There is concern that decisions are not being properly recorded when using these methods, raising questions as to how information is being managed, how it is stored, how it could be shared with others, and how it could be disclosed to Canadians.

In some institutions, non-essential staff had limited network access. This posed challenges for managing information and responding to access requests for this information. Some archaic practices, such as paper-based processes, became even more inefficient with restricted on-site access.

The pandemic has also jolted the process of adapting to technological advances, such as improving telework capacity for institutions and ATIP units across government. The use of electronic transmissions of documents, e-signatures and the shift from paper documents to electronic ones are all helping the access system. It should be noted that best practices are being shared across institutions through various interdepartmental networks, which should be encouraged and commended.

At the end of 2020–2021, most institutions were still negatively impacted by on-site restrictions and remote work. In fact, while some improved their capacity during the year, many institutions were still operating at limited capacity as of March 31, 2021.

There has been a lack of responsiveness on the part of some offices of primary interest, the program areas within institutions tasked with responding to access requests received by ATIP units.

While it is true that some offices of primary interest were deeply involved in the government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis and were required to balance their additional responsibilities with responding to access requests, this lack of responsiveness may also stem from complacency in the area of access.

This culture of complacency is characterized by the view that responding to access requestsis a distraction from employees’ day jobs, rather than what it actually is: a core part of their responsibility as public servants—to facilitate transparency in government operations.

Among the observations compiled by the OIC over the course of investigations completed in 2020–2021, the following could also be beneficial to any institution seeking to improve its performance in the area of access.

Respecting the 30-day time limit

All government institutions should be reminded that the 30-day time limit to respond to requests is not merely a suggestion. It is the law, subject to validly claimed extensions of time. The downplaying or tolerance of invalid extensions and delays must end.

All institutions must take every necessary measure to ensure they respect the letter and the spirit of Act. As statistics from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and the many complaints dealt with by the OIC indicate, adherence to the Act is often not the case.

Sharing useful and valuable information

Beyond the need for better tools for documenting key actions and decisions, a full culture shift across institutions is required on how useful and valuable government information is shared. Many Canadians simply do not have access to the information that would enable them to understand policies and question government decisions.

This is why the practice of voluntary disclosure, in addition to the legislative proactive disclosure requirements, must be more widely adopted. Institutions need to be transparent from the outset and disclose more information as a matter of course and independently of their legal obligations to do so.

The application of this principle, which is at the heart of a government that is open by default, can mitigate the number of access requests institutions receive. That said, the information voluntarily disclosed must be truly relevant to the public and allow a better understanding of the government’s decisions and policies. This is why proactive disclosure practices that involve indiscriminate dumping of data that is not of interest, or the publication of trivial information as a method to pay lip service to transparency and openness, do not fully uphold to this principle.

To identify the information in which the public is very interested, institutions can leverage their internal access to information expertise. Indeed, when information of value is not easily accessible, people turn to the access to information regime. Correspondence units can also be a good source of questions frequently asked and subjects of interest to citizens.

Investing in human resources

Without losing sight of the goal of addressing the high volume of access requests, there is an urgent government-wide need to adequately invest in human resources in the field of access to information, by creating pools, hiring sufficiently qualified staff and developing appropriate ongoing training for employees. Section 96 of the Act allows for a government institution to “provide services related to any power, duty or function conferred or imposed on the head of a government institution under this Act to another government institution that is presided over by the same Minister”.

The creation of a central pool of “surge capacity”, with experienced resources moving from one institution to another depending on the needs, could also be explored at the federal level. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this team could have been deployed to smaller institutions who did not have the resources needed to face the crisis.

The creation of such a team could minimize the strong competition that exists between institutions for access specialists. Furthermore, partnerships with academia could be explored to develop expertise in access to information through means such as a certification program.

Adapting to a new reality

Maintaining our operations

Investing in our resources

The OIC’s Professional Development Program (PDP), which was set up to enable career progression for investigators, was reconfigured and expanded to more junior levels this year. As investigators move through the program, they are assigned more complex files. The expanded PDP was launched on April 1, 2020, to enable career progression for investigators from the entry-level on up. Given the commitment to invest in our resources, staff received feedback, training and mentoring necessary to graduate from the program.

When the permanent funding for additional investigators that the Commissioner had been seeking since the start of her mandate was secured in August 2020, the OIC was able to move quickly to increase its overall staffing complement, in spite of the ongoing remote work arrangements and the overall limitations of running hiring processes during a pandemic.

Portfolio approach

This year, the Investigations and Governance Sector took the opportunity to further bolster the portfolio approach introduced prior to the pandemic. This approach consolidates the management of both administrative and refusal complaints within each of the teams, giving each directorate overall responsibility for dealing with all types of complaints against their assigned institutions.

The fully implemented portfolio approach, coupled with the PDP, allows an investigator to develop an understanding of the type of information a particular grouping of institutions produces, as well as the application of the Act to the records at issue.

Information Technology

With staff working remotely throughout the year, the OIC saw an immense increase in demand for network access. The sudden move to mostly electronic operations and investigations meant accelerating the introduction of online platforms, such as MS Teams and SharePoint to provide employees with the ability to share documents and collaborate in a virtual environment. This shift also required the testing and launching of videoconferencing software and the introduction of online surveys and training platforms. Chat platforms further enhanced the OIC’s ability to operate fully in a virtual space.

The measures introduced during this period, including all-electronic investigations (moving to a paperless environment and digitizing all steps of the investigation process), online collaboration, flexibility, working remotely and others will continue to be central to the OIC’s operations in the future.

Governance

In 2020–2021, the OIC implemented a new governance structure that formalizes how the OIC operates, based on the Commissioner’s priorities. For example, a new Web and Social Media Governance Committee now oversees the OIC’s intranet, internet and social media presence, with input from across the organization. The governance structure is also designed to permit the creation of new ad hoc bodies, as well as providing several forums for employee input and information sharing.

More than ever this past year, the well-being of the OIC’s employees has been front and centre as a priority for the Commissioner and her management team. While the Senior Management Committee meets weekly, an engaged executive cadre is also well represented and fully engaged in the work of the various corporate committees, including in the Workplace Health, Safety and Wellness Committee.

Finally, a new Departmental Results Framework has been developed and published to better reflect the Commissioner’s priorities. Set to come into effect in 2021–2022, it will also guide the development of key performance indicators and goals to achieve in investigations.

Focussing on the future

Beyond 2020

The year 2020–2021 saw the implementation of the OIC’s first business continuity plan (BCP) and the formation of the BCP Committee. Early in the pandemic, this committee met twice a week with the Commissioner and deputy commissioners to share information, respond to strategic direction, and put operational decisions into action, as well as report to central agencies on COVID-19 measures and the status of operations. In order to facilitate remote work arrangements and foresee the transition back to a “normal” post-pandemic work environment, the BCP Committee was eventually succeeded by Beyond 2020. This working group was tasked with developing the OIC’s vision for its workplace of the future, along with guiding principles that would help chart a course for the organization during the months to come.

During 2020–2021, Beyond 2020 helped ensure employees could work effectively at home by undertaking a survey of equipment needs. The group also issued a roadmap for the return to the workplace that set out several stages for the return and the requirements for each. The roadmap was shared with all staff, and followed up with communication from the Commissioner through a monthly virtual all-staff meeting, known as the Commissioner’s Hour.

Over time, the group increasingly turned its focus to setting a vision for the OIC of the future. The increase in hiring that the permanent funding afforded had already led the OIC to begin considering whether its existing office space could be renovated, or whether additional space would be required in the future. However, the ongoing success of remote work has changed the focus to what the OIC’s true needs are in terms of physical space and how it will conduct business in the future.

Supporting our team

The year 2020–2021 was the first of the new five-year strategic plan, introduced in the fall of 2020. The plan established a new vision and mission for the organization, along with five new values and three strategic pillars to guide the work of the organization over the next five years. With one of the pillars being “Invest in and support our resources,” the OIC carried out two surveys on employee mental health, in order to gauge how employees were managing to work at home; assess the kind of support they required; and hear their views on returning to the workplace.

The OIC also reviewed and updated its telework directive and its code of values and ethics, and introduced programs and services through providers such as the Ombudsperson for Mental Health. Through a Memorandum of Understanding with Health Canada, the OIC’s capability to pursue external investigations of harassment complaints or wrongdoing has increased.

A three-year program of activities and resources to support employee mental health is being updated in accordance with feedback garnered through staff surveys, with revised strategies and a detailed action plan to be launched in 2021–2022. The OIC will also be working to foster diversity and inclusion in the workplace, welcoming and valuing the contributions of women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, and members of racialized groups and LGBTQ2 communities.

In the early months of the pandemic

The Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan (RBAEP) and the Departmental Security Plan (DSP) were the OIC’s primary reference for risk. These are comprehensive documents that were updated with input from across the organization. The OIC took the risks it identified into consideration when it updated the Business Continuity Plan (BCP) in early 2020 and implemented it in the early months of the pandemic. The frequent BCP meetings were a forum for addressing immediate risks, grounded in the RBAEP.

About the Office of the Information Commissioner

Canada’s Access to Information Act came into force in 1983, permitting Canadians to retrieve information from government files. The Act established what information could be accessed and mandated timelines for response.

The Office of the Information Commissioner was established that same year to support the work of the Information Commissioner of Canada. The OIC carries out confidential investigations into complaints about government institutions’ handling of access requests, giving both complainants and institutions the opportunity to present their positions.

The OIC seeks to maximize compliance with the Act, using the full range of tools, activities and powers at the Commissioner’s disposal. These include negotiating with complainants and institutions without the need for formal investigations, and making recommendations and/or issuing order to resolve matters at the conclusion of investigations. The OIC also supports the Information Commissioner in her advisory role to Parliament and parliamentary committees on all matters pertaining to access to information. It also actively makes the case for greater freedom of information in Canada through targeted initiatives such as Right to Know Week and ongoing dialogue with Canadians, Parliament and government institutions.

The Commissioner is supported by a staff of approximately 135 employees led by three deputy commissioners responsible for investigations and governance, legal services and public affairs, and corporate services, strategic planning and transformation services.

Appendix – Annual report of the Information Commissioner Ad Hoc

While it has been a trying year for all of us in both our personal and professional lives, I was pleased to be able to continue being of service to all those who called upon me for assistance.

In that regard, many individuals took the time to write, presenting their concerns, with thorough representations and documentation in support. Such concerns resulted from both ongoing OIC complaint investigations and their outcomes.

The authority delegated to me as Information Commissioner Ad Hoc does not allow me to review the OIC’s investigations of complaints involving other public bodies, which are matters that must be pursued before the courts and as such fall outside of my review area. Nonetheless, I took care in replying to them, explaining why I cannot act. Furthermore, I informed the OIC of such cases, thereby enabling that Office to better address those concerns with the individuals directly, as the case may be.

From April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, I received a total of 42 matters, of which 20 were individual files.

- Notification from the OIC: 1 (time extension, no complaint ensued)

- Non-receivable complaints: 9

- Complaints under investigation: 32

- Timeliness of OIC response: 2 (both resolved)

- Determination - no further investigation necessary/not receivable: 28 (out of time, outside jurisdiction, etc.)

- Report of Findings - merits OIC response: 2 (no recommendation)

Of the complaints reviewed this year, two were the subject to a Report of findings into the lawfulness of the responses issued by OIC pursuant to access to information requests. In both complaints, I found that the responses were issued in accordance with the rules under the Act, with no further recommendation. Of interest was the subject matter : the requesters sought access to the contents of OIC complaint investigation files.

As I have dealt with similar cases in the past, I believe it appropriate to highlight the rules relied upon by the OIC when deciding to grant or refuse access to requested information found in its complaint investigation files.

The Act grants to every person the right to request and be given access to any record under the control of a government institution, which includes the Office of the Information Commissioner, which itself is subject to the Act.

In some cases, this right of access can be lawfully limited, thereby allowing requested information to be withheld. Doing so may result in a complaint, which is every requester’s right under the Act. A complaint resulting from an access request made to the OIC is directed to the Commissioner Ad Hoc, who has been appointed to investigate complaints against the OIC.

There is a common understanding that the public’s access to information contained in files of public law enforcement and legal investigation authorities is limited and will depend on factors such as the identity of the person requesting, the subject matter under investigation, and the timing of the request itself (whether during or, at the conclusion of the law enforcement process/legal investigation).

The Act recognizes this fact and has extended this principle to the OIC (as well as other parliamentary officers):

16.1(1) The following heads of government institutions shall refuse to disclose any record requested under the Act that contains information that was obtained or created by them or on their behalf in the course of an investigation, examination or audit conducted by them or under their authority:

(a) the Auditor General of Canada;

(b) the Commissioner of Official Languages for Canada;

(c) the Information Commissioner; and

(d) the Privacy Commissioner.

Simply put, this provision legislates a limit on access to records that are the subject of audits, examinations, investigations, therefore, an exemption to the otherwise broad right of access. Subsection (1) of section 16.1 spells out that any information the OIC obtains and records in its investigation files can never be disclosed. In other words, the OIC has no choice but to refuse access to that type of requested information. Subsection (2) of section 16.1, on the other hand, operates as an exception to that rule:

16.1(2) However, the head of a government institution (…) shall not refuse (…) to disclose any record that contains information that was created by them or on their behalf in the course of an investigation (…) conducted by them or under their authority (…) once the investigation or audit or and all related proceedings, if any, are finally concluded. (Emphasis added)

The words I have underlined focus upon information that was created during an investigation, as opposed to that which was obtained as noted in the first subsection shown above. This means that information the OIC created during its investigation must be disclosed where requested, although there is one precondition before access can take place. That is that the complaint investigation itself must first be concluded.

During my review of these cases, another observation was raised: the source of the requested information. We know that the OIC has separate divisions which carry out various work tasks, including investigations. Individuals request information from the OIC that has been recorded in other divisions of the OIC, such as its investigations unit. The Act, however, does not give consideration for the source of the requested information. For that reason, the OIC has adopted the practice of considering its divisions as separate from one another for the purpose of applying access to information rules referred to above.

For instance, requests for access to information are submitted to the OIC ATIP Secretariat. In the case where the requester seeks access to information found in the files of another division of the OIC, the OIC ATIP Secretariat must treat that division as a separate, stand alone source, just as if it were from another institution. As the OIC ATIP Secretariat processes the request, it will receive records from the other division that house the information relevant to the request.

The rules for disclosure are then applied as follows: any information the OIC complaint investigation obtained (during the investigation of the complaint) is said to be ‘information obtained’, and for that reason, it can never be disclosed to the individual requesting it. In those same records, however, information that the OIC complaint investigation created during its investigation is said to be ‘information created’, and for that reason, it can be disclosed to the requester when the investigation is concluded.

In such cases, the resulting disclosure of requested information can be admittedly difficult to comprehend, because we perceive the OIC as one single entity. However in the cases I have reviewed to date, I have found that the OIC’s practice and assessment of the information it reviews as having been obtained or created has been efficient and lawful.

To summarize, and with a view to inform the public and highlight the application of the important rules regarding access to information found in the investigation files of the OIC, I note that:

- information that was obtained by the OIC (such as collected from the OIC complaint investigations) can never be disclosed by the OIC;

- information that was created by the OIC (such as created by the OIC complaint investigations) can be disclosed by the OIC to the person requesting, provided that the OIC complaint investigation in question is concluded; and

- the OIC considers its complaint investigation division as a separate source for the purpose of applying these two rules when processing access to information requests.

In closing, I hope my Annual Report has articulated a helpful insight of the work I do as Ad hoc Commissioner and trust that it will likewise serve a useful purpose. I look forward in continuing to be of service to those who will seek my assistance in the coming year.

Respectfully submitted,

Anne E. Bertrand, Q.C./c.r.

Ad hoc Commissioner