2015 Chapter 4: Maximizing disclosure

The purpose of the Access to Information Act is to provide a right of access to all records under the control of institutions that are subject to the Act.

The purpose of the Access to Information Act

2(1) The purpose of this Act is to extend the present laws of Canada to provide a right of access to information in records under the control of a government institution in accordance with the principles that government information should be available to the public, that necessary exceptions to the right of access should be limited and specific and that decisions on the disclosure of government information should be reviewed independently of government.

The Act says that the general right of access may be restricted when necessary by limited and specific exceptions. There is also a presumption in favour of disclosure imposed on institutions.Footnote 1 Balancing the right of access against claims to protect certain information is at the core of the access to information regime.

The Act also requires that decisions on disclosure should be reviewed independently of government. The Commissioner and the courts provide this independent oversight.

Under the Act, many exemptions are not sufficiently limited and specific, nor are some subject to independent review. In addition, they are not generally in line with national and international norms. Moreover, the number of exemptions to the right of access has increased since the Act came into force.Footnote 2

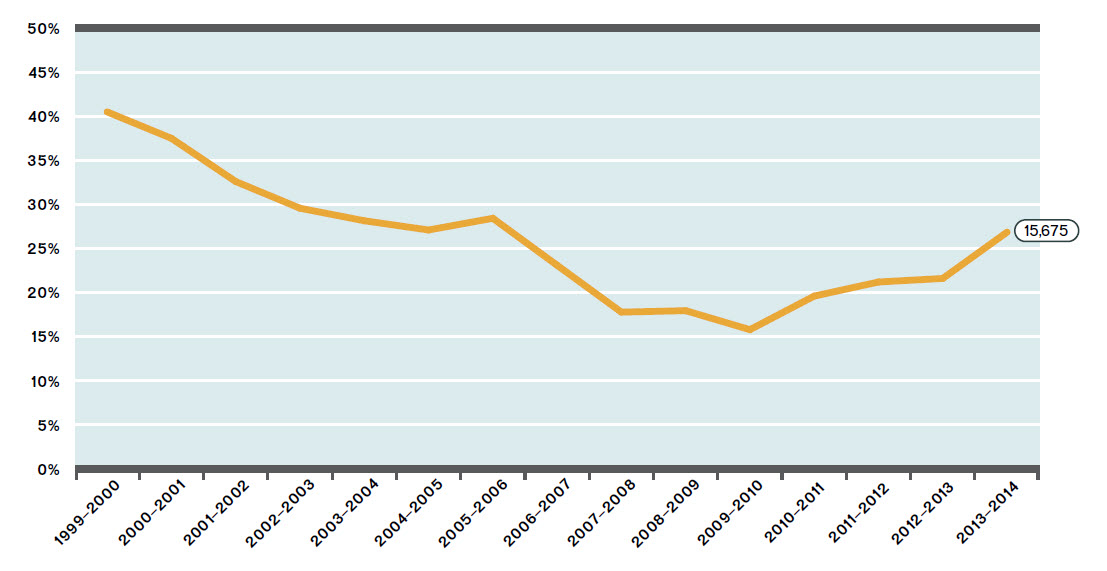

Although more requests are being made and more pages are being released in response to access to information requests, the percentage of requests resulting in all information being disclosed has declined.

Figure 1: Proportion of requests completed in which all information was disclosed (1999-2000 to 2013-2014)Footnote 3

Text Version

Graph description: The present line graphic describes the proportion of requests closed for which all the information was disclosed for the reporting periods 1999-00 to 2013-14. The proportion of requests all disclosed went down from 40.5% in 1999-00 to 15.79% in 2009-10. In 2013-14 the proportion was back to 26.85% (or 15,675 requests). The proportions by reporting period are as follows:

| Reporting period | 1999-2000 | 2000-2001 | 2001-2002 | 2002-2003 | 2003-2004 | 2004-2005 | 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 40.5% | 37.5% | 32.6% | 29.57% | 28.15% | 27.10% | 28.43% | 23.10% | 17.78% | 17.95% | 15.79% | 19.60% | 21.20% | 21.60% | 26.85% |

In 1999–2000, 40.5 percent of all requests resulted in all information being disclosed. In 2013–2014, this number stood at 26.9 percent.

A modern access law must be developed in the context of the Open Government initiative and the government’s commitment to be open by default.Footnote 4 The exemptions in the Act need to be comprehensively reviewed to maximize disclosure of information. This will result in:

- a meaningful open by default culture in the government;

- an Act that is aligned with the most progressive national and international norms; and

- an effective access to information regime that fosters transparency, accountability and citizen engagement.Footnote 5

How the Act currently protects information

The Act protects information through the use of exemptions and exclusions.

Exemptions

Exemptions permit or require institutions to withhold a range of records and information from disclosure.The Act contains the following categories of exemptions:

- Class-based or injury-based exemptions: Class-based exemptions prevent disclosure of information based solely on whether it falls within a specified class of information. The exemption for personal information is an example of a class-based exemption. Injury-based exemptions require that a harms test be applied in order to determine whether disclosure would prejudice the interest the exemption protects.

- Mandatory or discretionary exemptions: Mandatory exemptions prohibit disclosure of information once it has been determined that the exemption applies. As a result, the institution in control of the information is under a legal obligation to refuse access. The mandatory exemptions in the Act usually apply to information that was obtained by an institution and does not belong to it. Discretionary exemptions permit an institution to refuse disclosure based on a two-step process. First, the institution must determine whether the exemption applies. Second, when it does, the institution must determine whether the information should nevertheless be disclosed based on all relevant factors.

In some cases, information covered by an exemption may still be disclosed when a condition is met, for example, if consent is obtained or where the information is publicly available.

In other instances, the exemption includes express permission to disclose the information when the public interest in disclosure clearly outweighs the importance of protecting the information.

Exclusions

Exclusions provide that the Act does not apply to certain records or information. In some cases this removes independent oversight.

Exemptions

To protect only what requires protection, the exemptions in the Act must be limited and specific. Exemptions that are overly broad result in information being withheld when it should be disclosed. Overly broad exemptions also make the application of the Act more complex and lead to institutions applying multiple and overlapping exemptions to the same information at the same time.

To maximize disclosure, model laws promote exemptions that are:Footnote 6

- injury-based;

- discretionary;

- time-limited;

- subject to a public interest override; and

- subject to independent oversight.Footnote 7

Injury-based

Injury-based exemptions take into account the fact that the level of sensitivity attached to information changes as circumstances, time and perspective change. In contrast, for class-based exemptions, all that must be demonstrated is that the information falls within that class.Footnote 8

Discretionary

Discretionary exemptions allow for a case-by-case assessment on disclosure. Case law in Canada has established that discretion must be exercised in a reasonable manner, taking into account all relevant factors.Footnote 9 For discretion to be reasonably exercised, the institution must provide evidence that it considered whether information falling within the exemption claimed could nonetheless be disclosed, depending on the specific facts of the particular request and the interests involved.Footnote 10 In comparison, a mandatory exemption prohibits disclosure of information once it has been determined that the exemption applies.

Time-limited

Exemptions that are time-limited create greater certainty in access laws. As soon as the time limit is reached or the specified event (such as publication) takes place, institutions may no longer invoke the exemption to withhold the information.

Public interest override

Former Information Commissioner John Grace:

The lack of a general public interest override in the Act has been called “a serious omission which should be corrected.”

Office of the Information Commissioner, 1993–1994 Annual Report.

A public interest override in an access law allows for the competing interest of the public’s right to know to be balanced against the interest the exemption protects.Footnote 11 The decision-maker must determine if non-disclosure is necessary and proportionate as compared to the public’s interest in the information.

In making that determination, a number of factors related to the public interest in the information must be taken into account. Examples of relevant factors to consider include:

- open government objectives, such as whether the disclosure would support accountability of decision-makers, citizens’ engagement in public policy processes and decision-making, or openness in the expenditure of public funds;

- whether there are environmental, health or public safety implications; and

- whether the information reveals human rights abuses or would safeguard the right to life, liberty or security of the person.

Public interest overrides can be found in model laws, most of the national access to information laws that are among the top-10 of the Global Right to Information Rating and some provincial laws.Footnote 12 In addition, both the Tshwane Principles and the Organization of American States model law include a higher presumption in favour of disclosure for information related to human rights or crimes against humanity.Footnote 13

Currently, the Act contains only limited public interest overrides, and these are only applicable to a few sections.Footnote 14

A general public interest override must be added to the Act to ensure that the public interest in disclosure is taken into account while considering whether to apply any of the exemptions within the Act.

This override should include a non-exhaustive list of factors to be considered.

Recommendation 4.1

The Information Commissioner recommends that the Act include a general public interest override, applicable to all exemptions, with a requirement to consider the following, non-exhaustive list of factors:

- Open Government objectives;

- environmental, health or public safety implications; and

- whether the information reveals human rights abuses or would safeguard the right to life, liberty or security of the person.

Independent oversight

Exemptions to the right of access in the Act are independently reviewable. However, this oversight can be limited when information is protected by an exclusion from the coverage of the Act.

For example, it is clear that when an exemption is invoked, the Commissioner has access to all records during her investigation so that she may independently review the decision on disclosure. This is not always the case with exclusions. The exclusions in the Act differ from one to another. No two exclusions have the same wording or produce the same effects. Determining what records the Commissioner may obtain in the conduct of her investigations is assessed on a case-by-case basis.

An exclusion that limits oversight results in a weakened right of access. For this reason, model access laws recommend that all information controlled by an institution should be subject to the access law, with no exclusions for certain kinds of information.Footnote 15

In light of these considerations, the Commissioner recommends removing all exclusions from the Act and replacing them with exemptions, unless an exemption already exists to protect the interest at issue.

Recommendation 4.2

The Information Commissioner recommends that all exclusions from the Act should be repealed and replaced with exemptions where necessary.

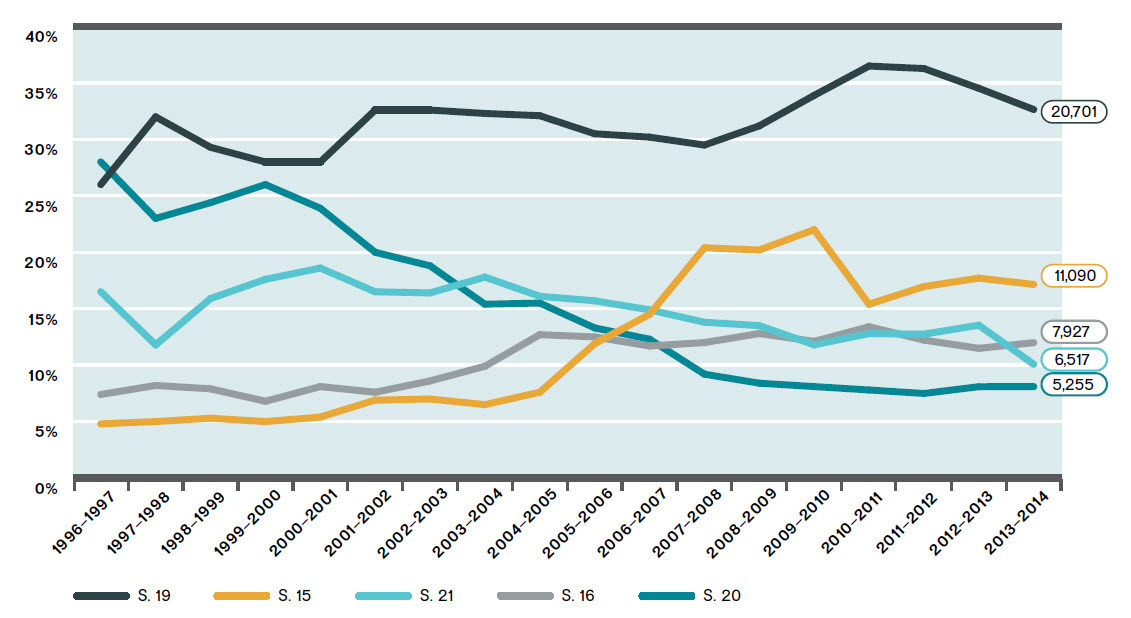

The graphic below presents the five most commonly applied exemptions between 1996–1997 and 2013–2014. They are: personal information (section 19), international affairs and defence (section 15), operations of government (section 21), law enforcement and investigations (section 16) and third party information (section 20).

Figure 2: Top 5 exemptions (1996–1997 to 2013–2014)

Text Version

This lines graphic presents the five most frequently invoked exemptions for the period 1996-1997 to 2013-2014. They are: personal information (section 19), international affairs and defence (section 15), operations of government (section 21), law enforcement and investigations (section 16) and third party information (section 20).

Exemptions in the graphic are presented as a proportion of all exemptions invoked during each reporting period. The proportions are as follows:

| Reporting period | Personal information (s.19) | International affairs and defence (s.15) | Operations of government (s. 21) | Law enforcement and investigation (s.16) | Third party information (s. 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996-1997 | 26% | 4.8% | 16.5% | 7.4% | 28% |

| 1997-1998 | 32% | 5% | 11.8% | 8.2% | 23% |

| 1998-1999 | 29.3% | 5.3% | 15.9% | 7.9% | 24.4% |

| 1999-2000 | 28% | 5% | 17.6% | 6.8% | 26% |

| 2000-2001 | 28% | 5.4% | 18.6% | 8.1% | 23.9% |

| 2001-2002 | 32.6% | 6.9% | 16.5% | 7.6% | 20% |

| 2002-2003 | 32.6% | 7% | 16.4% | 8.6% | 18.8% |

| 2003-2004 | 32.3% | 6.5% | 17.8% | 9.9% | 15.4% |

| 2004-2005 | 32.1% | 7.6% | 16.1% | 12.7% | 15.5% |

| 2005-2006 | 30.5% | 11.9% | 15.7% | 12.5% | 13.3% |

| 2006-2007 | 30.2% | 14.5% | 14.9% | 11.7% | 12.3% |

| 2007-2008 | 29.5% | 20.4% | 13.8% | 12% | 9.2% |

| 2008-2009 | 31.2% | 20.2% | 13.5% | 12.8% | 8.4% |

| 2009-2010 | 33.9% | 22% | 11.8% | 12.1% | 8.1% |

| 2010-2011 | 36.5% | 15.4% | 12.8% | 13.4% | 7.8% |

| 2011-2012 | 36.3% | 17% | 12.7% | 12.2% | 7.5% |

| 2012-2013 | 34.5% | 17.7% | 13.5% | 11.5% | 8.1% |

| 2013-2014 | 32.7% | 17.6% | 15.8% | 12.2% | 8.3% |

The proportion of exemptions applied under section 19 has increased from 26% in 1996–1997 to 32% in 2013–2014, with a peak of 36.5% in 2010–2011. Use of section 15 has also increased. Exemptions under this section represented 5% of all exemptions applied in 1996–1997, the proportion was 22% in 2009–2010 (with a slight decrease to 17% by 2013–2014). Use of section 16 has fluctuated by about five percentage points during this same period (from 7% in 1996–1997 to 12% in 2013–2014). There was a general downward trend in the use of section 21 between 1996–1997 and 2013–2014. However, it is believed that the decrease in 2013-2014 is due to a statistical error in the Info Source Bulletin. Finally, the proportion of exemptions applied under section 20 decreased significantly, from 28% in 1996–1997 to 8% in 2013–2014.

Exemptions and exclusions reviewed in this chapter

- Information obtained from other

governments (sections 13, 14 and 15) - National defence (sections 15 and 69.1)

- Law enforcement and investigations

(section 16) - Personal information (section 19)

- Third party information (section 20)

- Advice (section 21)

- Solicitor-client privileged information

(section 23) - Cabinet confidences (section 69)

- Exemptions for information protected

by other laws or for specific agencies

(sections 24, 16.1–16.4, 18.1, 20.1, 20.2,

20.4, 68.1 and 68.2)

Information related to other governments (sections 13, 14 and 15)

The Government of Canada holds information related to its dealings with other governments. This information falls into two main categories: The government may hold information that has been obtained in confidence from another government, or it may hold information related to its positions, plans and strategies in intergovernmental negotiations and relations.

There is a public interest in protecting both kinds of information. Other governments must be able to rest assured that information communicated to the Government of Canada in confidence will indeed be kept confidential.Footnote 16 Without this assurance, they would be far less likely to share this kind of information.Footnote 17 There is also a need to protect relationships between governments. The disclosure of certain information could injure relationships.

To protect these interests, the Act currently contains the following exemptions:

- Section 13 provides a mandatory, class-based exemption for information obtained in confidence from foreign governments, international organizations of states, governments of the provinces, municipal or regional governments and certain specific Aboriginal governments.

- Section 14 provides a discretionary, injury-based exemption for information the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the conduct by the Government of Canada of federal-provincial affairs.

- Section 15 provides a discretionary, injury-based exemption for information which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the conduct of international affairs.Footnote 18

Information obtained in confidence (section 13)

Section 13 provides a mandatory, class-based exemption for information obtained in confidence from a foreign government, international organizations of states, governments of the provinces, municipal or regional governments and certain specific Aboriginal governments.

Section 13 was invoked 2,470 times in 2013–2014.

This section protects confidential information belonging to other governments or international organizations of states. This information was not created by the Government of Canada and was transmitted to the Government of Canada by another government in confidence.

There is a public interest in the sharing of confidential information between governments: It fosters intergovernmental collaboration and cooperation. Other governments and organizations would be less likely to share information with Canada if they lost confidence in the ability of the Government of Canada to protect their confidences. Accordingly, the mandatory exemption found in the Act is justified.Footnote 19, Footnote 20

The Act provides two limitations on this strict prohibition. Information obtained in confidence from another government or international organization of states may be disclosed if consent is obtained, or if the originating government or organization makes the information publicly available. However, there is no incentive to respond to consultation requests for consent to disclose, and in fact other governments rarely do. This leads to overuse of this exemption, particularly for historical records.

Consulting with other levels of government within Canada is generally a straightforward exercise, as the heads of these governments or institutions are easily identified and located, and most are subject to similar access regimes within their own jurisdictions. Consultations should be mandatory in these circumstances.

Recommendation 4.3

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to seek consent to disclose confidential information from the provincial, municipal, regional or Aboriginal government to whom the confidential information at issue belongs.

There are different considerations at the international level that make a mandatory obligation to consult inappropriate. International consultations can be complicated by protocols of formal diplomatic channels of correspondence, language issues or government instability. Given these considerations, at the international level, consultation should always be undertaken when it is reasonable to do so.Footnote 21

Recommendation 4.4

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to seek consent to disclose confidential information of the foreign government or international organization of states to which the confidential information at issue belongs, when it is reasonable to do so.

To address the observed lack of response from other governments to requests for consent, it is necessary to require that, where consultation has been undertaken, consent is deemed to have been given if the consulted government does not respond within 60 days. It would therefore be incumbent on the government or organization whose interest is being protected to indicate that it does not wish the information to be disclosed. Footnote 22, Footnote 23

Recommendation 4.5

The Information Commissioner recommends that, where consultation has been undertaken, consent be deemed to have been given if the consulted government does not respond to a request for consent within 60 days.

The current Act provides that in circumstances where consent to disclose is given, or the information is made public, institutions may disclose the information. This exemption should be directive rather than discretionary: An institution shall not refuse to disclose information on the basis of section 13 where consent has been obtained, or where the information has been made publicly available by the originating government or organization.

Recommendation 4.6

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to disclose information when the originating government consents to disclosure, or where the originating government makes the information publicly available.

Section 14 provides a discretionary, injury-based exemption for information which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the conduct by the Government of Canada of federal-provincial affairs.

Section 15 includes a discretionary, injury-based exemption for information which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the conduct of international affairs.

Section 14 was invoked 990 times in 2013–2014.

Section 15 as it relates to international affairs was invoked 2,346 times in 2013–2014.

Harm to inter-governmental affairs (sections 14 and 15)

The Government of Canada holds information related to its positions, plans and strategies in negotiations and relations between itself and other governments, at both the provincial and international levels.

The interest that requires protection in this case is the government’s ability to conduct business, cooperate and negotiate across jurisdictions. This interest is protected in the Act on a discretionary basis, where the government can show that disclosure could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the conduct of international affairs (in section 15) or federal-provincial affairs (in section 14).Footnote 24

In drafting the Act, the word “affairs” was selected by the government to ensure that the protection in this exemption would extend beyond actual negotiations to also encompass positions leading up to negotiations, as well as negotiation strategies.Footnote 25 However, the term “affairs” is too broad to protect this interest. The word should therefore be replaced with more specific terms, such as “negotiations” and “relations.”Footnote 26 This is consistent with other access laws and clearly circumscribes the protection to the interests to be protected: positions taken during the course of inter-governmental deliberations, and the diplomatic conduct of relationships between governments.Footnote 27

Recommendation 4.7

The Information Commissioner recommends replacing international and federal-provincial “affairs” with international and federal-provincial “negotiations” and “relations.”

To further clarify that these provisions contain a similar interest, the Commissioner recommends combining these provisions into a single exemption that protects inter-governmental negotiations and relations. This would leave a single interest protected under section 15: national security.

Recommendation 4.8

The Information Commissioner recommends combining the intergovernmental relations exemptions currently found in sections 14 and 15 into a single exemption.

Section 15 provides a discretionary, injury-based exemption for information the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the defence of Canada or any state allied or associated with Canada or the detection, prevention or suppression of subversive or hostile activities.

Section 15 as it relates to national security was invoked 8,744 times in 2013–2014.

National security (sections 15 and 69.1)

The Government of Canada holds a wide range of information relating to national security, from plans related to military operations to human source reports.

Recent disclosures about the surveillance activities of national security bodies have raised citizens’ concerns and resulted in calls for greater transparency. The Tshwane Principles, which offer guidance to countries on how to balance access to information with national security interests, underscore that legitimate national security interests are, in practice, best protected when the public is well informed about the state’s activities, including those undertaken to protect national security.Footnote 28 Making this type of information available to the public contributes to informed debate on important issues or matters of serious interest and enhances government accountability.

National security is protected in the Act by a discretionary exemption that allows institutions to refuse to disclose this information only where potential injury can be shown to defence, or the detection, prevention or suppression of subversive or hostile activities. Although the Act contains no specific reference to “national security,” these two interests are sufficiently defined at section 15(2) so that the scope of protection for national defence is limited and specific.

However, the Commissioner’s investigations have revealed an overuse of section 15 for historical information, particularly documents that have been transferred to Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Although the Federal Court noted in the Bronskill decision that “the passage of time can assuage national security concerns”,Footnote 29 some of this information continues to be classified at a confidential, secret, or even top secret level, a fact that complicates the assessment of injury in the disclosure of these documents.Footnote 30

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Security Organization and Administration Standard requires that information be “classified or designated only for the time it requires protection, after which it is to be declassified or downgraded.” The Standard also indicates that departments should provide for automatic declassification when the information is created or collected.Footnote 31 Departments must develop with LAC agreements to declassify or downgrade sensitive information transferred to the control of LAC. The Standard also recommends that an automatic expiry date of 10 years should apply to secret, confidential and low-sensitive designated information. The Commissioner’s investigations have revealed that this Standard does not appear to have been implemented by institutions.

The Government’s Directive on Open Government and Action Plan speak to the removal of access restrictions or the declassification of departmental information resources of enduring value prior to transfer to LAC or as it occurs within LAC. However, the Directive and the Plan do not speak of a systematic review, nor do they talk of the implementation of a declassification process for its government records of enduring value. To provide the flexibility needed to adequately protect national security interests while maximizing disclosure, the Commissioner recommends a mandatory obligation on the part of institutions to declassify information on a routine basis.Footnote 32, Footnote 33

To be clear, declassified documents could still be legitimately withheld under the national security exemption if the injury test is met. However, a routine review of documents with a view to declassification would greatly help those tasked with the determining injury or non-injury and could result in more timely access to information, particularly in historical records.Footnote 34

Recommendation 4.9

The Information Commissioner recommends a statutory obligation to declassify information on a routine basis.

Certificates issued by the Attorney General (section 69.1)

In addition to section 15, the Act also includes another protection for information related to national security. Section 69.1 is a mandatory exclusion for information that has been certified as confidential under section 38.13 of the Canada Evidence Act (CEA).Footnote 35

Section 38.13 of the CEA empowers the Attorney General to personally issue a certificate in connection with a proceeding for the purpose of protecting information obtained in confidence from, or in relation to, a foreign entity or for the purpose of protecting national defence or national security. The expressions “national defence” or “national security” are not defined.

When a certificate under this section is issued, it terminates all proceedings under the Act related to a complaint, including an investigation by the Commissioner, an appeal or a judicial review. After this point, the Information Commissioner has no authority to review the information in dispute or the application of the exclusion.Footnote 36

This section was added to the Act in 2001 under the Anti-terrorism Act.Footnote 37 To the Commissioner’s knowledge, the certification process has never been used to prevent disclosure under the Act.

There are a number of significant issues with section 69.1 when it is assessed in light of the purpose of the Act.Footnote 38

- It is not subject to independent oversight, which hinders the ability to strike the right balance between the right of access and non-disclosure.

- The lack of definition for “national defence” or “national security”, as well as other ambiguities that have been identified with section 38.13 of the CEA, result in an overly broad scope to the exclusion.Footnote 39

- It is unnecessary, as section 15 is adequate to protect national security.

Recommendation 4.10

The Information Commissioner recommends repealing the exemption for information certified by the Attorney General (section 69.1).

Law enforcement and investigations (section 16)

Section 16 contains two discretionary, class-based exemptions for:

- Information of listed investigative bodies that pertains to the detection, suppression or prevention of crime, the enforcement of a law, or threats to the security of Canada, if the record is less than 20 years old (section 16(1)(a));

- Information relating to investigative techniques or plans for specific lawful investigations (section 16(1)(b)).

Section 16 contains two discretionary, injury-based exemptions for:

- Information the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the enforcement of any law, or the conduct of lawful investigations (section 16(1)(c));

- Information the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the security of penal institutions (section 16(1)(d));

- Information that could reasonably be expected to facilitate the commission of an offence (section16(2)).

Further, section 16(3) provides a mandatory exemption prohibiting the disclosure of information that was obtained or prepared by the RCMP while performing policing services for a province or municipality, if the Government of Canada has agreed not to release this information.

Section 16 was invoked 7,758 times in 2013–2014.

The Government of Canada holds a wide range of information related to law enforcement, including RCMP investigation files, penitentiary records, parole board files, citizenship and immigration files, and tax audit files.

Generally, the interest that section 16 protects is the enforcement of laws. While it is of public importance that law enforcement authorities’ work not be impeded by the disclosure of information, there is also an important public interest in the ability to scrutinize the activities of law enforcement bodies.

A discretionary exemption that requires evidence of a reasonable expectation of injury strikes the appropriate balance between these interests.

The scope of this exemption must be narrowed so that it protects only what is legitimately necessary. After 30 years of experience, it is clear that section 16(1)(c), which protects information which if disclosed could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the enforcement of any law, or the conduct of lawful investigations, sufficiently covers and adequately protects the law enforcement interest.

Sections 16(1)(a), 16(1)(b), and 16(3) are unnecessary and should therefore be repealed. This simpler structure would also streamline the application of this exemption by institutions and reduce the concurrent application of multiple exemptions.

The two other interests protected in this section, namely the security of penal institutions and the avoidance of illegal activity, are appropriately circumscribed by the protections in sections 16(1)(d) and 16(2) and do not require amendment.

Recommendation 4.11

The Information Commissioner recommends repealing the exemptions for information obtained or prepared for specified investigative bodies (section 16(1)(a)), information relating to various components of investigations, investigative techniques or plans for specific lawful investigations (section 16(1)(b)) and confidentiality agreements applicable to the RCMP while performing policing services for a province or municipality (section 16(3)).

Personal information (section 19)

Section 19 is a mandatory, class-based exemption prohibiting the disclosure of “personal information,” subject to certain exceptions.

The term “personal information” is defined by reference to the Privacy Act as, “information about an identifiable individual that is recorded in any form.” The definition also provides examples of what is and is not included within the meaning of personal information.

Institutions may disclose any record that contains personal information if

- the individual to whom it relates consents to the disclosure;

- the information is publicly available; or

- the disclosure is in accordance with section 8 of the Privacy Act.

Section 19 was invoked 20,701 times in 2013–2014.

The Government of Canada holds a significant amount of personal information. This information can be transmitted to the government voluntarily, as when a person submits comments regarding a local development project, or it can be required to be submitted, as is tax information. This information could be very sensitive, such as medical information, or fairly innocuous, such as the business contact information normally found on a business card or email signature.

The interest that requires protection here is personal privacy, which, in turn, connotes “concepts of intimacy, identity, dignity and integrity of the individual.”Footnote 40 This information belongs to identifiable individuals, and the risks of inappropriate disclosure may be quite serious to the individual. Therefore, protection of personal privacy warrants a mandatory prohibition on disclosure.

Not all disclosures of personal information result in an unjustified invasion of a person’s personal privacy. A balancing test that considers all of the relevant circumstances is needed in order to ensure that only information that merits protection is withheld.

Under the Act, personal information may only be disclosed where there is consent from the individual, the information is publicly available, or the disclosure is in accordance with section 8 of the Privacy Act, which sets out a list of circumstances in which a government institution may disclose personal information.Footnote 41 There is one circumstance that provides for an injury-based assessment. This is where, in the opinion of the head of the institution, the public interest in disclosure clearly outweighs any resulting invasion of privacy. However, this rarely-used provision requires a public interest to be identified and weighed to justify disclosure, regardless of the kind or sensitivity of the personal information at issue.Footnote 42

Almost all provincial and territorial access laws contain an exception to the personal information exemption where the disclosure would not constitute an “unjustified invasion of privacy.”Footnote 43 The decision-maker must consider all relevant circumstances. These include, but are not limited to, criteria listed in the statute. Examples include whether the disclosure is desirable for the purpose of subjecting the activities of government to public scrutiny; whether the information is highly sensitive; and whether disclosure may unfairly damage the reputation of any person referred to in the record.

In addition, most statutes list circumstances in which disclosure of personal information is presumed to be an unjustified invasion of personal privacy. This includes, for example, personal information relating to medical history. Most statutes also list circumstances in which disclosure is presumed not to be an unjustified invasion of personal privacy. This includes, for example, personal information that discloses financial or other details of a contract for personal services between the individual and an institution.

An injury-based approach to the disclosure of personal information strikes the appropriate balance between access and privacy.Footnote 44 It creates a spectrum of protection, using presumptions of injury or non-injury depending on the kind of information at issue, while also allowing for these presumptions to be rebutted, based on the particular circumstances and context of the information. This spectrum ensures the protection of sensitive personal information, and maximum disclosure of non-sensitive personal information.Footnote 45

Recommendation 4.12

At issue in Information Commissioner v Minister of Natural Resources Canada, 2014 FC 917, was whether basic professional information, consisting of the names, titles and workplace contact information of private sector employees appearing in records responsive to a request under the Act is “personal information” warranting exemption under section 19(1).

The Commissioner argued that the meaning and scope of “personal information”should be informed by individuals’ rights of privacy (which, in turn, connote “concepts of intimacy, identity, dignity and integrity of the individual”) and that, as a result, information that would generally appear on an individual’s business card cannot be considered “personal information.”

The Federal Court rejected this argument, concluding instead that all information “about” an identifiable individual is “personal information” unless it falls within one of the exceptions to the definition of “personal information” set out in section 3 of the Privacy Act.

The Information Commissioner recommends amending the exemption for personal information to allow disclosure of personal information in circumstances in which there would be no unjustified invasion of privacy.

In addition, the Commissioner’s investigations have revealed two specific instances in which the section 19 exemption for personal information requires modification: business contact information and compassionate disclosure.

Some laws that protect personal privacy specifically exclude from the definition of personal information business contact information. For example, the Personal Information and Protection of Electronic Documents Act, which establishes the rules to govern the collection, use and disclosure of personal information by the private sector, excludes from its definition of “personal information” the names, titles, business addresses and telephone numbers of an employee of an organization.Footnote 46 The access and privacy laws of Alberta, Ontario and New Brunswick also exclude business contact information from the definition of personal information. This information should similarly be excluded from the definition of “personal information.”

Recommendation 4.13

The Information Commissioner recommends that the definition of personal information should exclude workplace contact information of non-government employees.

In addition, many of the provincial access laws allow disclosure to the spouse or close relatives of a deceased person, as long as it would not result in an unreasonable invasion of the deceased’s privacy.Footnote 47 The Commissioner has encountered investigations where this information is not disclosed because a “public interest” could not be identified. It is the Commissioner’s view that the Act should explicitly allow for compassionate disclosure, as long as the disclosure is not an unreasonable invasion of the deceased’s privacy.

Recommendation 4.14

The Information Commissioner recommends including a provision in the Act that allows institutions to disclose personal information to the spouses or relatives of deceased individuals on compassionate grounds, as long as the disclosure is not an unreasonable invasion of the deceased’s privacy.

Finally, the Act currently provides that in circumstances in which consent to disclose is given, institutions may disclose the information. This is problematic in two respects. First, the Act is silent as to when an institution should seek the consent of an individual. Second, this provision has, in some instances, been interpreted to refuse disclosure even in circumstances in which the individual has consented. To ensure that the interest protected is the personal privacy of the individual, institutions should be explicitly required to seek consent whenever it is reasonable to do so. Further, institutions should be obligated to disclose personal information where the individual to whom the information relates has consented to its disclosure.

Recommendation 4.15

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to seek the consent of the individual to whom the personal information relates, wherever it is reasonable to do so.

Recommendation 4.16

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to disclose personal information where the individual to whom the information relates has consented to its disclosure.

Section 20 contains three mandatory, class-based exemptions for:

- a third party’s trade secrets (section 20(1)(a));

- financial, commercial, scientific or technical information that is confidential information supplied to a government institution by a third party and is treated consistently in a confidential manner by the third party (section 20(1)(b));

- information supplied in confidence by a third party when it relates to preparation, maintenance, testing or implementation by a government institution of emergency management plans that concern the vulnerability of the third party’s buildings or other structures, its networks or systems or the methods used to protect any of those buildings, structures, networks or systems (section 20(1)(b.1)).

It also contains two mandatory, injury-based exemptions for:

- information which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to result in financial loss or gain to a third party or could reasonably be expected to cause prejudice to a third party’s competitive position (section 20(1)(c));

- information whose disclosure could reasonably be expected to interfere with a third party’s contractual or other negotiations (section 20(1)(d)).

Institutions may disclose information with a third party’s consent. Further, institutions have the discretion to disclose third party information (with the exception of a third party’s trade secrets) when such disclosure would be in the public interest as it relates to public health, public safety or protection of the environment, and provided the public interest in disclosure clearly outweighs any loss or gain to the third party.

This section was invoked 5,255 times in 2013–2014.

Third party information (section 20)

The Government of Canada collects a wide range of information from third parties, Footnote 48 including trade secrets and other confidential commercial information, market research, business plans and strategies, and internal inspection and testing results. This information may be submitted voluntarily, such as in a bid for a government contract, or submitted as required by law, for example as proof of regulatory compliance.

There is a compelling need to protect information that is provided to the government by third parties. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, “such information may be valuable to competitors and disclosing it may cause financial or other harm to the third party who had to provide it. Routine disclosure of such information might even ultimately discourage research and innovation.”Footnote 49

Given the public interest in encouraging business development and innovation, the potentially serious economic consequences of disclosure, and the fact that third party information is not owned by the government, this is an instance in which a mandatory exemption is justified.

In 2008, Canada Post Corporation (CPC) received a request for “contracts given to Wallding International” dating from 1997 to 2000. In response, CPC withheld details about a contract that awarded a monthly $15,000 retainer to Wallding for general advice on broadly worded subject areas. In part, the justification for non-disclosure was based on some of the exemptions found in section 20.

The Commissioner was not convinced that CPC had properly applied the exemptions found in section 20.

As required by the Act, the Commissioner sought representations from the former president of Wallding. She was not persuaded by his representations, which focused entirely on the potential damage to him in his personal capacity. The Commissioner therefore recommended that the information be disclosed.

In the end, CPC disclosed all the details of the contract.

However, the protection offered in section 20 must also be balanced against the need for transparency regarding public-private partnerships and the need for accountability in both government contracting practices and awards. It must also take into account the government’s regulatory function of the private sector.

Therefore, the mandatory exemption should be limited by an injury test. It should only apply to specific types of third party information where disclosure could reasonably be expected to cause significant harm to a third party’s competitive or financial position, or where disclosure could result in similar information no longer being supplied voluntarily to the institution.

The Commissioner therefore recommends a mandatory exemption for trade secrets or scientific, technical, commercial or financial information, supplied in confidence, when the disclosure could reasonably be expected to:

- significantly prejudice the competitive position or interfere significantly with the contractual or other negotiations of a person, group of persons, or organization;

- result in similar information no longer being supplied voluntarily to the institution when it is in the public interest that this kind of information continue to be supplied;

- result in undue loss or gain to any person, group, committee or financial institution or agency.

Such an amendment, when paired with the Commissioner’s recommendation that all exemptions be subject to a general public interest override, would:

- focus the exemption so that it protects certain third party information when disclosure could reasonably be expected to cause significant harm;

- streamline this exemption, thus reducing the concurrent application of multiple overlapping exemptions;

- make the protections for third party information consistent with provincial laws;Footnote 50 and

- in conjunction with the Commissioner’s recommendation in Chapter 3 that a third party is deemed to consent to disclosing its information when it fails to respond to a consultation request within appropriate timelines, give an incentive to third parties to provide adequate representations to institutions to establish proof that harm would result if the information were to be disclosed.

Recommendation 4.17

The Information Commissioner recommends a mandatory exemption to protect third-party trade secrets or scientific, technical, commercial or financial information, supplied in confidence, when the disclosure could reasonably be expected to:

- significantly prejudice the competitive position or interfere significantly with the contractual or other negotiations of a person, group of persons, or organization;

- result in similar information no longer being supplied voluntarily to the institution when it is in the public interest that this type of information continue to be supplied; or

- result in undue loss or gain to any person, group, committee or financial institution or agency.

The Act provides that in circumstances where consent to disclose is given by a third party, institutions may disclose the information. This exception should be directive rather than discretionary: An institution shall not refuse to disclose information on the basis of section 20 when the third party has consented to disclosure.

Recommendation 4.18

The Information Commissioner recommends requiring institutions to disclose information when the third party consents to disclosure.

The application of section 20 is narrowed when such disclosure would be in the public interest as it relates to public health, public safety or protection of the environment, and provided the public interest in disclosure clearly outweighs any loss or gain to the third party. In these instances, institutions have the discretion to disclose a third party’s information.

Given the Commissioner’s recommendation that all exemptions be subject to a general public interest override, this limited public interest override can be repealed.

Recommendation 4.19

The Information Commissioner recommends that the limited public interest override in the third party exemption be repealed in light of the general public interest override recommended at Recommendation 4.1.

The application of the exemption for third parties should be limited in one other instance. Under the Act, institutions can apply third party exemptions to protect information about grants, loans or contributions that have been given to a third party by the government (as long as the information meets the criteria of the exemption as currently constructed).

Given that grants, loans and contributions are publicly funded, the public has an interest in knowing how this money is spent. The Commissioner therefore recommends increasing the level of transparency surrounding grants, loans and contributions by providing that section 20 cannot be applied to information about them, including information related to the status of repayment and compliance with the terms (See Chapter 7 for a broader discussion on proactive disclosure related to grants, loans and contributions).

This will aid the public in tracking the types, amounts, recipients and repayment of grants, loans and contributions, and keep institutions accountable for their decisions surrounding these types of financial support.

Recommendation 4.20

The Information Commissioner recommends that the third party exemptions may not be applied to information about grants, loans and contributions given by government institutions to third parties.

Advice and recommendations (section 21)

Section 21 is a discretionary, class-based, time-limited exemption for advice or recommendations developed by or for an institution or a minister of the Crown.

This exemption also applies to accounts of consultations or deliberations, positions or plans for negotiations carried on or to be carried on by or on behalf of the government or plans relating to managing personnel or the administration of institutions that have not been implemented.

The exemption applies to records that came into existence fewer than 20 years prior to the request.

Section 21 does not apply to:

- accounts or statements of reasons for a decision that is made in the exercise of a discretionary power or an adjudicative function and that affects the rights of a person; and

- a report prepared by a consultant or an adviser who was not a director, an officer or an employee of a government institution or a member of the staff of a minister of the Crown at the time the report was prepared.

Section 21 was invoked 6,517 times in 2013–2014.

Policy- and decision-making is at the heart of government. As this encompasses much of the daily business of government, institutions hold a vast amount of information related to policy- and decision-making.

There is a public interest in protecting the policy- and decision-making processes of government. If all policy- and decision-making information were disclosed, there is a risk that public officials may not provide full, free and frank advice. This, in turn, could impair the effective development of policies, priorities and decisions.

There is an equally important public interest in providing citizens with the information needed to be engaged in public policy and decision-making processes, to have a meaningful dialogue with government, and to hold government accountable for its decisions.

Section 21 is a class-based, discretionary exemption that protects a wide range of information relating to policy- and decision-making. However, the exemption in its current form extends far beyond what must be withheld to protect the provision of free and open advice. The breadth of this exemption must be narrowed to strike the right balance between the protection of the effective development of policies, priorities and decisions on the one hand, and transparency in decision-making on the other.

First, the section should only protect information which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the provision of free and open advice and recommendations.Footnote 51

Successive information commissioners have indicated that the exemption for advice and recommendations is problematic.

Inger Hansen (1983–1990)

Section 21, permitting the exemption of advice and accounts of consultations and deliberations, is probably the Act’s most easily abused provision.

Annual Report 1987–88John Grace (1990–1998)

The advice and recommendations exemption, together with the exclusion of Cabinet confidences, ranks as the most controversial clause in the Access to Information Act.

Annual Report 1992–1993John Reid (1998–2006)

The exemption for advice and recommendations is one of the most controversial provisions of the Act as its broad language can be made to cover – and remove from access – wide swaths of government information.

Open Government Act: Notes

Recommendation 4.21

The Information Commissioner recommends adding a reasonable expectation of injury test to the exemption for advice and recommendations.

Second, the Act should extend the list of explicit examples of information that will not fall within the scope of the exemption.Footnote 52

At present the list is limited to:

- an account or a statement of reasons for a decision that is made in the exercise of a discretionary power or an adjudicative function and that affects the rights of a person; and

- a report prepared by a consultant or an adviser who was not a director, an officer or an employee of a government institution or a member of the staff of a minister of the Crown at the time the report was prepared.Footnote 53

The list should also include factual materials, public opinion polls, statistical surveys, appraisals, economic forecasts and instructions or guidelines for employees of a public institution.Footnote 54

Recommendation 4.22

The Information Commissioner recommends explicitly removing factual materials, public opinion polls, statistical surveys, appraisals, economic forecasts, and instructions or guidelines for employees of a public institution from the scope of the exemption for advice and recommendations.

Third, in light of the public interest in citizen engagement and the government’s Open Government commitments, the 20-year time frame included in section 21 is unnecessarily long.Footnote 55 This time limit should be reduced to provide certainty as to when the exemption can no longer be applied.

Recommendation 4.23

The Information Commissioner recommends reducing the time limit of the exemption for advice and recommendations to five years or once a decision has been made, whichever comes first.

Section 23 is a discretionary, class-based exemption for information subject to solicitor-client privilege.

Section 23 was invoked 2,132 times in 2013–2014.

Solicitor-client privilege (section 23)

Institutions frequently engage the services of legal professionals. As a result, institutions hold information that stems from these relationships, such as legal opinions, factums of law, routine communications and fee invoices.

The Act contains an exemption to protect information that is subject to solicitor-client privilege. Solicitor-client privilege is not defined in the Act; however, the courts have clarified that the exemption covers both legal advice privilege and litigation privilege.Footnote 56

Section 23 was recently considered in Canada (Information Commissioner of Canada) v Canada (Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness) et al., 2012 FC 877.

A requester sought access to a copy of a protocol between the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Department of Justice regarding the principles governing the listing and inspection of RCMP documents within the context of civil litigation.

Requests for this protocol were sent to both the RCMP and the Department of Justice. In response, both institutions refused to disclose the protocol based on section 23, as well as another exemption.

The Court was asked to determine whether the protocol contained information subject to solicitor-client privilege and, if so, whether discretion to refuse access was reasonably exercised.

The Court held that most of the protocol was not protected by solicitor-client privilege, because it was “a negotiated and agreed-upon operational policy formulated after any legal advice has been given and after any continuum that is necessary to be protected in light of the purposes behind the privilege.” It was impossible to tell whether the protocol was based on earlier legal advice. Thus, disclosing the document does not disclose the content of any earlier legal advice.

Legal advice privilege recognizes that the justice system depends on the vitality of full, free and frank communication between those who need legal advice and those who are best able to provide it. The resulting confidential relationship between solicitor and client is a necessary and essential condition of the effective administration of justice and the public’s confidence in the legal system.Footnote 57 Legal advice privilege is of unlimited duration.

Litigation privilege, in contrast, is aimed at ensuring the efficacy of the adversarial process by creating a zone of privacy that allows litigants to “prepare their contending positions in private, without adversarial interference and without fear of premature disclosure.”Footnote 58 It applies to documents that were created for the dominant purpose of existing, contemplated, or anticipated litigation. Litigation privilege is of temporary duration, automatically coming to an end upon the termination of the litigation that gave rise to its existence.

Given the importance of the protection of solicitor-client privilege to the proper functioning of the legal system, a class-based, discretionary exemption for solicitor-client privilege should be maintained.

Unlike litigation privilege, the indefinite application of section 23 as it relates to legal advice privilege in the public sector is problematic.

Contrary to organizations in pursuit of private goals, the government’s mandate is to pursue the public interest. This public interest aspect of government administration justifies differences in the operation of solicitor-client privilege. The government’s public interest mandate provides heightened incentive to waive privilege to ensure greater transparency and accountability.Footnote 59 Therefore, factors such as whether the protection is still relevant, whether the advice is old and outdated, or the historical value of the advice carry more weight in favour of disclosure.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) received a request for all records in a file concerning an individual involved in the Halifax Explosion disaster of 1917. LAC refused to disclose certain information in this file, stating it was still subject to solicitor-client privilege, as per section 23 of the Act.

The requester, who is a professional historian and author who needed the requested information for an upcoming publication, complained to the Commissioner about the denial of access.

The Commissioner asked LAC if it would exercise its prerogative as client to waive solicitor-client privilege and release the information to the requester, as it would be in the public interest.

During the investigation it was revealed that LAC consulted with the Department of Justice, who confirmed that the requested information was still covered by solicitor-client privilege and recommended that it be withheld.

Based on that recommendation, LAC withheld the records. However, it did not consider disclosing the information in the public interest, as the Commissioner had requested. The Commissioner asked LAC again to carry out this assessment.

During a second consultation with the Department of Justice, LAC was advised that the documents in question were actually under the control of either Transport Canada or Fisheries and Oceans Canada, even years after the event to which they refer occurred. This effectively made one of these two institutions the actual “client” and, as such, responsible for exercising the required discretion.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada replied that the records were not under its control. Transport Canada reviewed the information and, after careful consideration, determined that it held no litigation value and waived the solicitor-client privilege. LAC subsequently released all records to the requester.

The Commissioner therefore recommends that this exemption, as it applies to the legal advice privilege, be subject to a time limit of 12 years after the last administrative action on the file.Footnote 60 This is consistent with the practice at the Department of Justice to transfer to LAC legal opinions 12 years after the last administration action on the file because the information no longer has any business value.Footnote 61

Recommendation 4.24

The Information Commissioner recommends imposing a 12-year time limit from the last administrative action on a file on the exemption for solicitor-client privilege, but only as the exemption applies to legal advice privilege.

The Commissioner has observed that section 23 is frequently applied to withhold legal counsel’s billing information.

In common law, this information is presumed privileged. However, in the case of aggregate total amounts billed, this presumption of privilege can frequently be rebutted on the grounds that the information is neutral and, as such, the disclosure of total billing amounts would not prejudice the interest that solicitor-client privilege is intended to protect.Footnote 62

Given that legal fees associated with the work done by counsel retained by institutions are funded by taxpayers, the Commissioner recommends that section 23 cannot be applied to aggregate total amounts of fees paid. This will help the public track how much money institutions spend on legal issues and keep institutions accountable for their decisions to engage legal services.

Recommendation 4.25

The Information Commissioner recommends that the solicitor-client exemption may not be applied to aggregate total amounts of legal fees.

Section 69 excludes confidences of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada. This includes Cabinet confidences and confidences of the Privy Council and Cabinet committees, such as Treasury Board (hereinafter “Cabinet confidences”).

The exclusion sets out a non-exhaustive list of types of records that constitute a Cabinet confidence, that includes:

- memoranda to cabinet (69(1)(a));

- discussion papers (69(1)(b));

- agenda of Cabinet or records recording deliberations or decisions of Cabinet (69(1)(c));

- records used for or reflecting certain communications or discussions between ministers (69(1)(d));

- records intended to brief Ministers in relation to matters (69(1)(e));

- draft legislation (69(1)(f));

- any record that contains information about the contents of any record referred to in sections 69(1)(a) to (f) (69(1)(g)).

The exclusion does not apply to:

- Cabinet confidences that are more than 20 years old; or

- discussion papers, when the decision to which the paper relates has been made public or four years have passed since the decision was made.

Section 69 was invoked 3,136 times in 2013–2014.Footnote 1a

Cabinet confidences (section 69)

Cabinet is responsible for setting the policies and priorities of the Government of Canada. In doing so, ministers must be able to discuss issues within Cabinet privately, so as to arrive at decisions that are supported by all ministers publicly, regardless of their personal views. The need to protect the Cabinet decision-making or the deliberative process is well established under the Westminster system of Parliament, and is known as Cabinet confidences. This need for protection has been recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada.Footnote 63

At present, Cabinet confidences are excluded from the right of access under the Act, subject to certain limited exceptions. What is described as a Cabinet confidence in section 69(1) of the Act is overly broad and goes beyond what is necessary to protect the interest that the exclusion is intended to address – namely, Cabinet’s deliberative process.

Section 69(1) of the Act sets out a non-exhaustive list of types of records that are to be considered Cabinet confidences. This list includes records not traditionally considered to be part of the Cabinet paper system. For instance, pursuant to section 69(1)(g) even records containing information about the content of any Cabinet record are to be excluded.

Successive information commissioners have indicated that the Act’s exclusion for Cabinet confidences is problematic.

Inger Hansen (1983–1990)

[M]y concern was that the withholding of records under the exclusionary section should be minimal. [...] My personal opinion [...] was that a democracy would benefit by having access to that kind of material.

1989–1990 Annual ReportJohn Grace (1990–1998)

Perhaps no single provision brings the Access to Information Act into greater disrepute than section 69 which excludes Confidences of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada from the legislation's reach.

1993–1994 Annual ReportJohn Reid (1998–2006)

The last vestiges of unreviewable government secrecy – i.e. Cabinet confidences – should be brought within the coverage of the law and the review jurisdiction of the Commissioner. Cabinet confidentiality risks being broadly, and too self-servingly, applied by governments when it is free from independent oversight.

Remarks to the University of Alberta’s 2006 Access and Privacy ConferenceRobert Marleau (2007–2009)

The role of Cabinet in a Westminster system of Parliament and the need to protect the Cabinet decision-making process are well understood. However, experience in other provincial, territorial and international jurisdictions with Westminster-style governments has demonstrated that the deliberations and decisions of Cabinet can be properly protected without excluding them from the purview of the legislation.

Strengthening the Access to Information Act to Meet Today's Imperatives, presentation to the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics, March 2009Suzanne Legault (2009–present)

As I stated publicly, it is my deep conviction that, under the Access to Information Act, Cabinet confidences should be subject to an exemption, and not an exclusion [...] Similarly, the Office of the Commissioner should have the right to review them independently to determine whether they are in fact Cabinet confidences.

Evidence given to the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, March 16, 2011

Section 69(3) sets out some exceptions to the Cabinet confidences exclusion. According to this provision, discussion papers are not excluded if the decision to which the discussion paper relates has been made public or, if the decision has not been made public, when four years have passed since the decision was made.Footnote 64 However, as a practical matter, these exceptions may be unlikely to result in the disclosure of additional information. This is because what was known as a discussion paper in 1983 no longer exists as a result of changes to the Cabinet paper system.Footnote 65

An exemption for Cabinet confidences has been recommended in the following government or parliamentary documents:

- The Green Paper that was a precursor to the Access to Information Act

- Bill C-43, which was the bill that introduced the Act

- Open and Shut

- A Call for Openness, the 2001 report of the ad hoc Parliamentary Committee on Access to Information

- Making it Work for Canadians

- Private members bills C-554 and C-556

Also problematic is the fact that Cabinet confidences are currently excluded from the Act, and not just exempted from the right of access. This is unlike the protection afforded to Cabinet confidences in all but one Canadian province, as well as in Australia, the U.K. and New Zealand.Footnote 66

The fact that the Act excludes Cabinet confidences has significant repercussions on the Commissioner’s ability to provide effective oversight when investigating a complaint that concerns a government institution’s refusal to disclose records based on section 69(1). Based on current case law, the Commissioner cannot require that records claimed to be excluded under section 69(1) be provided to her office so that she can independently assess whether the records are in fact Cabinet confidences.Footnote 67 This means that the Commissioner cannot actually see or consider the substance of what is claimed to be excluded. Instead, the Commissioner must assess whether the exclusion applies based on tombstone descriptions of the records or circumstantial evidence concerning the record’s content.

The Commissioner recommends that Cabinet confidences be protected by a mandatory exemption when disclosure would reveal the substance of deliberations of Cabinet and, as is the case for all exemptions, that this exemption be subject to a general public interest override.Footnote 68 Such an exemption will sufficiently protect the interest that is intended to be protected, while ensuring that:

- claims of Cabinet confidences are subject to effective independent oversight;

- disclosure is based on the substance of the information at issue instead of the record’s format or title;

- the protection afforded to Cabinet confidences is consistent with the majority of national and international access laws.

Recommendation 4.26

The Information Commissioner recommends a mandatory exemption for Cabinet confidences when disclosure would reveal the substance of deliberations of Cabinet.

Most of the provincial access laws list types of information that cannot be withheld as a Cabinet confidence. A parliamentary committee and the task force mandated with reviewing the Act in 2002 also recommended that the Act mirror this approach.Footnote 69 Examples of the types of information that cannot be withheld include:

- information, the purpose of which is to provide background explanations or analysis to Cabinet for its consideration in making a decision, if the decision has been made public, has been implemented or more than a certain amount of time has passed since the decision was made or considered;

- purely factual or statistical information provided to Cabinet;

- analyses of problems or policy options that do not contain subjective information; and

- information in a record of a decision made by Cabinet when acting in its capacity as an appeal body.Footnote 70

Several jurisdictions in Canada that contain an exemption for Cabinet records provide that the exemption cannot be applied to records that are older than 15 years, rather than 20, as currently found in the Act.Footnote 71

Finally, the access laws in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario provide that the exemption for Cabinet confidences cannot be applied when the Cabinet for which the record has been prepared consents to access being given.Footnote 72

To facilitate citizens’ participation in the government’s decision-making process, the government needs to be more forthcoming with the information it relies upon to make decisions. The exemption for Cabinet confidences should allow for maximum disclosure. To accomplish this, the exemption should not apply to information other than what is necessary to protect Cabinet’s deliberative process and should be of limited duration.Footnote 73

Recommendation 4.27

The Information Commissioner recommends that the exemption for Cabinet confidences should not apply:

- to purely factual or background information;

- to analyses of problems and policy options to Cabinet’s consideration;

- to information in a record of a decision made by Cabinet or any of its committees on an appeal under an Act;

- to information in a record that has been in existence for 15 or more years; and

- where consent is obtained to disclose the information.

Given the sensitivity attached to Cabinet confidences, the Commissioner recommends that investigations of refusals to disclose pursuant to this exemption be delegated to a limited number of designated officers or employees within her office. Such a requirement would be consistent with section 59(2) of the Act, which limits the number of officers or employees who may investigate complaints related to international affairs or defence.

Recommendation 4.28

The Information Commissioner recommends that investigations of refusals to disclose pursuant to the exemption for Cabinet confidences be delegated to a limited number of designated officers or employees within her office.

Creating a law of general application

Restrictions to the right of access found in other laws

Section 24 is a mandatory exemption for any information the disclosure of which is restricted by a provision listed in Schedule II of the Act.

Section 24 was invoked 135 times in 2013–2014.

Section 4 of the Act provides that, notwithstanding any other act of Parliament, every person has a right to access and shall, on request, be given access to any record under the control of an institution. This section gives the Act precedence over any other act of Parliament. However, section 24 requires government institutions to withhold information protected by a series of statutory provisions listed in Schedule II of the Act (for example, sections of the Statistics Act and Criminal Code).Footnote 74

In addition, the precedence of the Act over any other act of Parliament may be impaired when recent legislation includes language intended to prevent disclosure of information, by using language such as “despite the Access to Information Act.”Footnote 75

Schedule II and the laws that contain language that is intended to supersede the Act affect the general right of access to government information. These provisions make it more difficult to understand what information can be obtained because determining whether or not the information falls within the mandatory exemption set out in section 24 frequently involves an analysis of complex provisions incorporated from other statutory regimes into the Act.

Successive information commissioners have indicated that section 24 and Schedule II are problematic.

Inger Hansen (1983–1990)

In our view, section 24 and the Schedule II statutes are not necessary at all to the working of the Access to Information Act, and in some instances give rise to unfairness and inconsistent treatment. We recommend their repeal.

Main brief to House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs, May 7, 1986John Grace (1990–1998)

These “by the back door” derogations from access rights are ... troubling to the Commissioner....The spirit and intent of the Access to Information Act can be whittled away by oft-ignored consequential amendment provisions buried at the back of other laws. For that reason, too, Parliamentarians have reason for concern. When Parliament adopted the right of access to government records it included a very important phrase: “notwithstanding any other Act of Parliament” (section 4). The continuing growth of Schedule II now threatens to erase the vital constraint on creeping secrecy which those six words originally gave.

Annual Report 1991–1992The Commissioner [is] also concerned that the process used to effect these changes [are] not by

direct amendments to the access Act. They [are] treated much like minor housekeeping amendments, tagged on to other bills. There [is] no debate; no discussion of the effects or the need for this type of an amendment. There [is] no consultation with the Commissioner’s office.

Annual Report 1992–1993John Reid (1998–2006)

The Access to Information Act contains a sweeping, catch-all provision. Section 24 requires that secrecy be maintained with respect to information made secret by another statute, if that other stature is referenced in Schedule II of the Access to Information Act.

Annual Report 1999–2000Connected with this notion, that the coverage of the Act should be comprehensive, is the notion that the Act should be a complete code setting out the openness/secrecy balance. No longer should we permit secrecy provisions in other statutes to be mandatory, in perpetuity, without meeting any of the tests for secrecy in the Act’s substantive exemptions. Section 24 of the Access to Information Act, which sets out this open-ended, mandatory, class exemption, should be abolished.

The Access Act – Moving Forward – A Commissioner’s Perspective, September 8, 2005Suzanne Legault (2009-present)

The inclusion of statutory provisions in Schedule II, and the resulting expansion of the mandatory class-based exemption found in section 24, has, in my opinion, resulted in the erosion of the right of access. It has done so by requiring government institutions to consider more than one statute in their decision-making process and making it more difficult for requesters to understand and exercise their access rights.