2014-2015 1. Highlights

This annual report sets out the activities of the Information Commissioner of Canada in 2014–2015. This chapter highlights noteworthy examples of the Commissioner’s investigations under the Access to Information Act and other related activities.

Access to information: Freedom of expression and the rule of law

In the fall of 2011, the government introduced a law to end the national long-gun registry, the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act (ELRA). This law required that all long-gun registry records be destroyed. Although the provisions of ELRA authorizing the destruction of these records specifically excluded the application of the Library and Archives Act and the Privacy Act, these provisions were silent with respect to the Access to Information Act.

In March 2012, an access request was made for the records in the registry. In April 2012, Parliament passed ELRA.

The Commissioner wrote to the Minister of Public Safety in April 2012 informing him that any records under the control of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for which a request had been received before ELRA came into force were subject to the right of access. The records should therefore not be destroyed until a response had been provided to the requester and any related investigation and court proceedings were completed. The Minister of Public Safety assured the Commissioner that the RCMP would abide by the right of access.

In January 2013, the RCMP responded to the request for the data in the registry. The requester then complained to the Commissioner about this response, alleging, among other things, that the response was incomplete. During her investigation in response to this complaint, the Commissioner learned that the majority of the long-gun registry records had, in fact, been destroyed. (The long-gun registry records relating to Quebec residents were maintained due to ongoing litigation.)

On March 26, 2015, the Commissioner wrote to the Minister to report that she had concluded that the response to the requester was incomplete. She formally recommended to the Minister that the RCMP process those remaining Quebec records she considered to be responsive to the request. She also recommended that the RCMP preserve those records until any proceedings related to the complaint were concluded.

The Minister declined to follow the Commissioner’s recommendation to process the Quebec records. He did confirm that the RCMP had preserved a copy of the relevant records.

Based on her investigation, the Commissioner was of the opinion that she had information relating to elements of the criminal offence set out in paragraph 67.1(1)(a) of the Act, which prohibits all persons from destroying records with the intent to deny a right of access. Also on March 26, 2015, the Commissioner referred information collected during this investigation relating to the destruction of the registry records to the Attorney General of Canada for possible investigation. No response has been received from the Attorney General about this referral. However, media reports indicate that the matter has been referred to the Ontario Provincial Police.

“On May 7, 2015, Bill C-59, the budget implementation bill, was tabled in Parliament. Division 18 of this bill makes the Access to Information Act non-applicable, retroactive to October 25, 2011, the date when the Ending the Long Registry Act was first introduced in Parliament. These proposed changes retroactively quash Canadians’ rights of access and the government’s obligations under the Act. They will effectively erase history.

It is perhaps fitting that this past Monday marked the anniversary of the publication of George Orwell’s 1984 and I quote: “Everything faded into mist. The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth. Every record has been destroyed or falsified...History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.”

If Bill C-59 passes as is, and it looks like it will, all records related to the destruction of the long gun registry will go through the Memory Holes of the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth.”

—Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault, speaking at the Access and Privacy Conference, 2015 in Edmonton, hosted by the University of Alberta's Faculty of Extension"

In May 2015, the government introduced Bill C-59, the Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1. Included in the bill were retroactive amendments to ELRA. As amended, ELRA would retroactively oust the application of the Access to Information Act to long-gun registry records, including the Commissioner’s power to make recommendations and report on the findings of investigations relating to these records. ELRA would also oust the right to seek judicial review in Federal Court of government decisions not to disclose these records. In addition, the legislation would retroactively immunize Crown servants from any administrative, civil or criminal proceedings with respect to the destruction of long-gun registry records or for any act or omission done in purported compliance with the Access to Information Act.

The Commissioner finalized her investigation and tabled a special report of her findings to Parliament in May 2015 while Bill C-59 was still before the House of Commons. She also expressed her serious concerns about the measures in Bill C-59 before both a House of Commons committee and a Senate committee. (See “On the record for an excerpt of her remarks before the Senate committee.)

No changes were made to Bill C-59 as it applied to ELRA after the committees’ reviews. The retroactive amendments became law on June 23, 2015.

Following the tabling of her special report, the Commissioner applied, with the consent of the complainant, to the Federal Court for a judicial review of the Minister’s refusal to release the records she had determined to be responsive to the request. As part of these proceedings, the Commissioner succeeded in obtaining an order from the Court requiring the Minister of Public Safety to deliver the hard drive containing the long-gun registry records for Quebec to the Federal Court Registry. The Government of Canada complied with this order on June 23, 2015.

The Commissioner also filed before the Ontario Superior Court of Justice an application challenging the constitutionality of ELRA as amended by Bill C-59. The Commissioner’s application seeks to invalidate these amendments on the grounds that they unjustifiably infringe the constitutional right of freedom of expression and that they contravene the rule of law by interfering with vested rights of access to this information.

The Commissioner’s application to the Federal Court for a judicial review of the Minister’s refusal to release the records responsive to the request was stayed in July 2015 pending the outcome of her constitutional challenge.

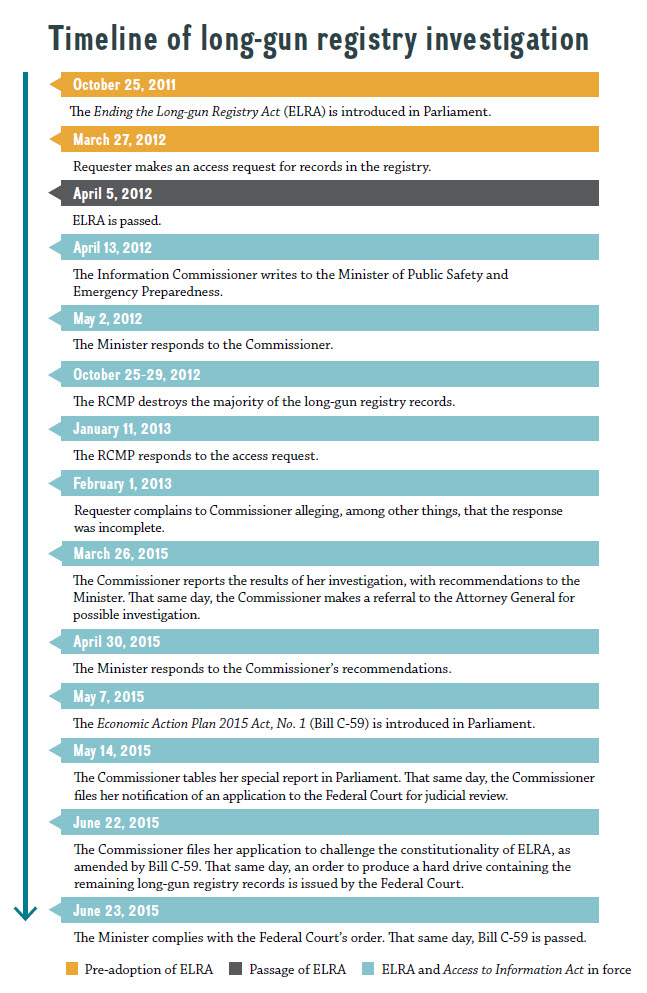

Timeline of Long-gun registry investigation

Text Version

- October 25, 2011 – The Ending the Long‐ gun Registry Act (ELRA) is introduced in Parliament.

- March 27, 2012 – Requester makes an access request for records in the registry.

- April 5, 2012 – ELRA is passed.

- April 13, 2012 – The Information Commissioner writes to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness.

- May 2, 2012 – The Minister responds to the Commissioner.

- October 25‐29, 2012 – The RCMP destroys the majority of the long-gun registry records.

- January 11, 2013 – The RCMP responds to the access request.

- February 1, 2013 – Requester complains to Commissioner alleging, among other things, that the response was incomplete.

- March 26, 2015 – The Commissioner reports the results of her investigation, with recommendations to the Minister. That same day, the Commissioner makes a referral to the Attorney General for possible investigation.

- April 30, 2015 – The Minister responds to the Commissioner’s recommendations.

- May 7, 2015 – The Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1 (Bill C‐59) is introduced in Parliament.

- May 14, 2015 – The Commissioner tables her special report in Parliament. That same day, the Commissioner files her notification of an application to the Federal Court for judicial review.

- June 22, 2015 – The Commissioner files her application to challenge the constitutionality of ELRA, as amended by Bill C-59. That same day, an order to produce a hard drive containing the remaining long-gun registry records is issued by the Federal Court.

- June 23, 2015 – The Minister complies with the Federal Court’s order. That same day, Bill C-59 is passed.

Access to information: Senators’ expenses

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner completed three investigations concerning the Privy Council Office’s (PCO) handling of requests for information related to various senators whose expenses and conduct were reported in the media.

Disclosing only meaningless information

The first investigation looked at PCO’s refusal to release 27 of 28 pages identified in response to a request for “any records created between March 26, 2013, to present (Monday, August 19, 2013) related to senators Mike Duffy, Mac Harb, Patrick Brazeau and/or Pamela Wallin.” In particular, the Commissioner examined PCO’s use of section 19 (Personal information), section 21 (Advice and recommendations) and section 23 (Solicitor-client privilege) to exempt whole pages of records.

Meaningful disclosure?

PCO agreed to sever and disclose the following types of information:

- signatures of public servants who had consented to their signatures being disclosed;

- date stamps;

- letterhead elements;

- Government of Canada emblems;

- the words “Dear” and “Sincerely”; and

- Document titles: “Memorandum for the Prime Minister”, “Memorandum for Wayne G. Wouters” and “Decision Annex.”

However, PCO refused to disclose the substance of the records. The Commissioner will seek the consent of the complainant to apply for a judicial review of PCO’s refusal of access.

The Commissioner found that portions of the records did not qualify for the claimed exemptions and that PCO also had not reasonably exercised its discretion to release information, bearing in mind relevant factors such as the public interest. She wrote to the Prime Minister (who is the “minister” of PCO) recommending that a significant amount of additional information be released.

PCO, on behalf of the Prime Minister, declined to implement the Commissioner’s recommendations, claiming that protection of the information “is appropriate.” However, PCO did agree to reassess the records with a view to severing and releasing any information it determined could be disclosed. As a result of this reassessment, small portions of information were released (see box, “Meaningful disclosure?” for a description of what was disclosed). PCO claimed, however, that this release of information was not required under the Act, because the information was “not intelligible, meaningless, or may be misleading.”

The information that was severed and released indicates that the records at issue consist of memoranda to the Clerk of the Privy Council, correspondence to and from the Clerk, a memorandum for the Prime Minister, signed and unsigned correspondence, a record of decision, and email exchanges to and from PCO officials. However, the substance of these documents remains protected.

Accessing records in the Prime Minister’s Office

Extending coverage

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended a number of measures to expand the coverage of the Act:

- establish criteria for determining which institutions would be subject to the Act, such as that all or part of the organization’s funding comes from the Government of Canada, that the organization is (in whole or in part) under public control or that it carries out a public function;

- extend coverage to ministers’ offices, including the Prime Minister’s Office;

- extend coverage to bodies that support Parliament, such as the Board of Internal Economy and the Library of Parliament; and

- extend coverage to bodies that provide administrative support to the courts.

PCO received a request for all records related to Senator Mike Duffy’s and Senator Pamela Wallin’s expenses for a particular time period. PCO responded that no such records existed. The requester complained to the Commissioner about this response.

During her investigation, the Commissioner asked PCO to carry out further searches within the institution, with the same result: no responsive records existed.

As a result of media reports outside the context of the Commissioner’s investigation, she learned that the email accounts of some departing PMO employees involved in the payment of Senate expenses that she had been told had been deleted, had been saved as part of ongoing litigation on another matter (CBC News, “Senate scandal: Benjamin Perrin's PMO emails not deleted”). The Commissioner followed up with PCO to determine whether these records were included in its searches. She ascertained that when the request was received, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) was not asked whether it had any records responsive to the request.

In response to the Commissioner’s inquiries, the relevant emails that were subsequently located within the email accounts of the departing PMO employees were disclosed to the Commissioner. Upon review, the Commissioner determined that these emails were not accessible under the Access to Information Act,since the Commissioner determined that these records did not meet the test for control as set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Information Commissioner) v. Canada (Minister of National Defence) et al., 2011 SCC 25. In this decision, the Court determined that ministers’ offices, including the Prime Minister’s Office, are not institutions subject to the Act. The Court did acknowledge, however, that some records located in ministers’ offices may be subject to the Act. A two-part test was devised for determining whether records physically located in ministers’ offices are “under the control” of an institution and therefore accessible under the Act.

This investigation highlights the accountability deficit created by the fact that ministers’ offices, including the PMO, are not covered by the Act.

Assessing information management and recordkeeping policies

Finally, news coverage about the automatic destruction of the email accounts of departing PMO employees, as well as correspondence to the Commissioner on this issue, prompted the Commissioner to initiate an investigation into PCO’s and the PMO’s information management and recordkeeping policies. Specifically, the Commissioner intended to investigate whether PCO’s stated internal practice of deleting email accounts of departing employees resulted in government records of business value being lost, thus preventing PCO from meeting its obligations under the Access to Information Act.

The Commissioner found that PCO and the PMO have a comprehensive suite of policies that align with the requirements of the Act, with the Library and Archives of Canada Act and with various Treasury Board policies. However, risks with these policies were identified. The main risk related to employees’ knowledge of their responsibilities with regard to the retention, deletion, storage and destruction of emails.

During the investigation, PCO reported that it had addressed these risks through its Recordkeeping Transformation Strategy; its Management Action Plan, which it developed after a 2011 horizontal audit of its electronic recordkeeping; and its three-year Risk-Based Audit Plan. The Commissioner reviewed these three documents and concluded that the measures PCO had put in place had mitigated the risks.

The Commissioner did not investigate the implementation of the policies. However, she did inform PCO that it should regularly audit the activities associated with its information management practices in order to meet its obligations under the Act. She also reported to PCO that it should proactively disclose the results of any audits it carries out related to information management.

Missing records at the Canada Revenue Agency

Missing records certification process with CRA

To ensure that requesters receive all the records to which they are entitled when making access requests to CRA, the Commissioner, in cooperation with CRA, has instituted a certification process.

Prior to the Commissioner closing a missing records complaint against CRA, the Assistant Commissioner or Director General of the identified branch or sector within CRA must certify that all reasonable steps were taken to conduct relevant searches to identify and retrieve responsive documents.

Since implementing this process in March 2015, the Commissioner has received approximately 20 such certifications.

There have been a number of instances in recent years in which the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) has found additional records during or after the completion of the Commissioner’s investigation into missing records complaints.

This issue first came to the forefront after a requester asked CRA for all records relating to the reassessment of her tax return. The requester complained that records were missing from the response she received. During the investigation, CRA informed the Commissioner that the records had been disposed of and could not be retrieved.

After the close of the Commissioner’s investigation, the requester sought a judicial review in the Federal Court of CRA’s use of exemptions on the records that were released. During these proceedings, CRA retrieved the records it previously said had been disposed of (Summers v. Minister of National Revenue, 2014 FC 880).

The second instance occurred during judicial review proceedings following the completion of the Commissioner’s investigations. The proceedings were initiated by seven numbered companies and were about CRA’s refusal to release portions of requested records (3412229 Canada Inc. et al. v. Canada Revenue Agency et al. (T-902-13); background; see also “Missing records”). After the commencement of those proceedings, the numbered companies alleged that there were additional records responsive to their requests that ought to have been disclosed. Since that time, CRA has released more than 14,000 additional pages.

The companies subsequently asked that the judicial review proceedings be put on hold until, among other things, the Commissioner investigated the possibility that more records existed. This investigation is ongoing.

In a third instance, the Commissioner investigated the release of 57 pages, with some exemptions, related to the audit of a taxpayer. The requester said that more documents should exist. During the investigation, CRA was asked to conduct additional searches and ensure that all the required offices had been tasked. This resulted in CRA disclosing an additional 57 pages to the requester in four supplementary releases, since records were found in each subsequent search.

Almost half of all CRA missing records complaints closed between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2015, were well founded (in contrast to the overall average of 27 percent for all institutions for the same period). CRA has acknowledged to the Commissioner that it has a serious information management and document retrieval problem when it comes to identifying and retrieving records in response to access requests. The Commissioner has instituted a certification process to provide additional assurances that all records have been properly identified and retrieved (see box, “Missing records certification process with CRA”).

The culture of delay

“...it is not enough for a government institution to simply assert the existence of a statutory justification for an extension and claim an extension of its choice. An effort must be made to demonstrate the link between the justification advanced and the length of the extension taken.”

Institutions “must make a serious effort to assess the required duration, and … the estimated calculation [must] be sufficiently rigorous, logic[al] and supportable to pass muster under reasonableness review.” [emphasis added]

Information Commissioner of Canada v. Minister of National Defence, 2015 FCA 56, paragraphs 76 and 79

In March 2015, the Federal Court of Appeal found that a three-year time extension taken by National Defence to respond to a request was unreasonable, invalid and constituted a deemed refusal of access. The request was for information about the sale of military assets (Information Commissioner of Canada v. Minister of National Defence, 2015 FCA 56; background, “Extensions of time (under appeal)”).

In its decision, the Court of Appeal first addressed whether the Federal Court had jurisdiction to review a decision by a government institution to extend the limit to respond to a request under the Act. The Federal Court had found that it had no such jurisdiction, but the Court of Appeal held that the Federal Court did have jurisdiction.

The determination of the jurisdiction issue involved deciding whether a time extension could constitute a refusal of access. Since the Federal Court’s jurisdiction is limited to instances of refusals (sections 41 and 42 of the Access to Information Act), the only route by which to challenge a government institution’s time extension is by way of a provision that deems government institutions to have refused access in certain circumstances (section 10(3)).

The Court of Appeal concluded that “a deemed refusal arises whenever the initial 30-day time limit has expired without access being given, in circumstances where no legally valid extension has been taken.”

A reading of the Act that would prevent judicial review of a time extension would, according to the Court of Appeal, fall short of what Parliament intended.

The Court of Appeal found that an institution may avail itself of the power to extend the time to respond to an access request, as provided by section 9 of the Act, but only when all the required conditions of that section are met.

The Court stated that “one such condition is that the period taken be reasonable when regard is had to the circumstances set out in paragraphs 9(1)(a) and/or 9(1)(b). If this condition is not satisfied, the time is not validly extended with the result that the 30-day time limit imposed by operation of section 7 remains the applicable limit.”

In its ruling, the Court of Appeal declared that “timely access is a constituent part of the right of access.”

In determining that the time extension asserted by National Defence was not valid, the Court found that National Defence’s treatment of the extension had fallen short of establishing that a serious effort had been made to assess the duration of the extension. It further noted that National Defence’s treatment of the matter had been “perfunctory” and showed that National Defence had “acted as though it was accountable to no one but itself in asserting its extension.”

This decision is expected to introduce much-needed discipline into the process of taking and justifying time extensions. It makes clear that extensions are reviewable by the Court and sets out standards to be met to justify the use and length of extensions.

The Commissioner will issue an advisory notice in 2015–2016 on how she will implement the Court of Appeal’s decision when conducting investigations.

Removing a barrier to access: Fees and electronic records

In February 2013, the Information Commissioner referred a question to the Federal Court to determine whether an institution could charge search and preparation fees for electronic documents that were responsive to requests made under the Access to Information Act (Information Commissioner of Canada v. Attorney General of Canada, 2015 FC 405; background, “Reference: Fees and electronic records”; summary).

This was the first time the Commissioner had brought such a reference under subsection 18.3(1) of the Federal Courts Act. The Court accepted that a reference under this provision was a valid mechanism for the Commissioner to seek guidance on a question or issue of law.

In the reference proceedings, the Commissioner took the position that “non-computerized records,” for which a search and preparation fee could be assessed under the Regulations of the Act, means records that are not stored in or on a computer or in electronic format.

On March 31, 2015, the Federal Court rendered its decision and agreed with the Commissioner’s interpretation that electronic records are not “non-computerized records.” This means that institutions must not charge fees to search for and prepare electronic records.

“There is a hint of Lewis Carroll in the position of those who oppose the Information Commissioner:

‘[w]hen I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean -- neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that’s all.-Information Commissioner of Canada v. Attorney General of Canada, 2015 FC 405, paragraph 65

The Court did not accept the arguments of the Attorney General and of the intervening Crown corporations that, following a contextual analysis, existing electronic records such as emails, Word documents and the like are non-computerized records.

The Court accepted the ordinary meaning of the words “non-computerized records” as being the correct interpretation of that expression. Its view was that “in ordinary parlance, emails, Word documents and other records in electronic format are computerized records” and records that are machine-readable are computerized.

The Commissioner will issue an advisory notice in 2015–2016 on how she will implement the Federal Court’s decision when conducting investigations.

Who controls the records?

The Commissioner investigated a complaint that a requester had not received from Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) all the relevant records in response to his request for information about building work carried out in relation to a health and safety complaint. A subcontractor to the principal contractor—the principal contractor was hired by PWGSC to provide building management services—had carried out the work.

Over the course of the investigation, the principal contractor found several batches of relevant records. Although these records were eventually disclosed to the requester, PWGSC claimed that they were not under its control, but rather under the control of the contractor. It asserted that it had no “legal or contractual obligation to retrieve documents” from third-party contractual service providers.

The Commissioner provided PWGSC with formal recommendations about its approach to retrieving records held by third-party contractual service providers, including the following: that PWGSC ensure that all records under its control, whether or not they are in its physical possession, are retrieved and processed in response to requests; that policies and supporting training to employees be implemented explaining the issue of control as it applies to contractors; and that PWGSC ensure that all contractors are aware of the requirements of the Act.

In its response to the Commissioner’s recommendations, PWGSC continued to maintain that the determination of whether PWGSC has control of a record held by a third party is established, in part, by determining whether it has the “legal or contractual obligation to retrieve documents.” The Commissioner has told PWGSC that this restrictive definition is inconsistent with the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision about the control of records and is inconsistent with accountable and transparent delivery of PWGSC’s provision of real property services.

This issue remains outstanding between the Commissioner and PWGSC, although PWGSC has agreed to continue to work with the Commissioner to reach a solution for future requests.

Recommendations for transparency

On March 30, 2015, the Commissioner released a special report to Parliament called Striking the Right Balance for Transparency. In this report, the Commissioner describes how the Access to Information Act no longer strikes the right balance between the public’s right to know and the government’s need to protect limited and specific information. She concludes that the Act is applied to encourage a culture of delay and to act as a shield against transparency, with the interests of the government trumping the interests of the public.

To remedy this situation, the Commissioner issued 85 recommendations in the report that propose fundamental changes to the Act, including the following:

- extending coverage to all branches of government;

- improving procedures for making access requests;

- setting tighter timelines;

- maximizing disclosure;

- strengthening oversight;

- disclosing more information proactively;

- adding consequences for non-compliance; and

- ensuring periodic review of the Act.

The Commissioner’s recommendations are based on the experience of the Office of the Information Commissioner with the Act, as well as comparisons to leading access to information models in provincial, territorial and international laws.

Updating the law becomes more urgent with each passing year. The Act came into force in 1983. Much has changed within government since that time, including how the government is organized, how decisions are made and how information is generated, collected, stored, managed and shared. The Open Government movement has increased Canadians’ expectations and demands for transparency. The law has not kept pace with these changes. There has been a steady erosion of access to information rights in Canada over the last 30 years that must be halted with a modernized access to information law.