The OIC started 2019–20 with more than 3,300 complaints in its inventory and then registered more than 6,000 new complaints.

Administrative complaints

Of the new complaints, 76 percent were administrative complaints (largely about delays in responding to access requests and about time extensions).

Most of these (70 percent) were against one institution, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), ranking it first on the OIC’s list of the top institutions that were subject to complaints in 2019–20.

The volume of IRCC complaints has not always been so large. In the two years prior to 2019–20, the OIC registered only 226 and 558 complaints against this institution, respectively. In July 2019, a small number of individuals began submitting large groups of complaints (nearly 70 in one week from one person, for example).

The complaints focused almost exclusively on the fact that IRCC had not responded to access requests within the legislated deadlines (either 30 days or an extended period) for the personal information of foreign nationals seeking to enter Canada either temporarily or permanently. Of particular note was that the number of time extension complaints against IRCC increased from just 12 in 2018–19 to 2,529 in 2019–20.

To better understand and address the root cause of these increases, the Commissioner initiated a systemic investigation against IRCC in March 2020 into the processing of access requests for client immigration files. The investigation will be completed in 2020–21.

The OIC closed 3,479 IRCC complaints in 2019–20, or 63 percent of the total. In many instances, the OIC’s initial inquiries determined that IRCC had already responded to the access requests.

Consequently, the OIC was able to quickly resolve 70 percent of the IRCC administrative complaints.

Complaints closed against IRCC and all other institutions, 2019–20

| Well founded | Not well founded | Resolved | Discontinued | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints closed against IRCC in 2019–20 | 20 | 32 | 3,374 | 53 | 3,479 |

| Complaints closed against all other institutions in 2019–20 | 577 | 312 | 683 | 477 | 2,049 |

| Total | 597 | 344 | 4,057 | 530 | 5,528 |

Refusal complaints

The OIC also receives complaints about institutions’ use of exemptions and exclusions to withhold information. These refusal complaints tend to take longer to investigate than administrative complaints. The OIC received 1,039 new refusal complaints (roughly the same amount as in 2018–19) and closed 1,253 in 2019–20, nearly equal to what the OIC achieved the year before.

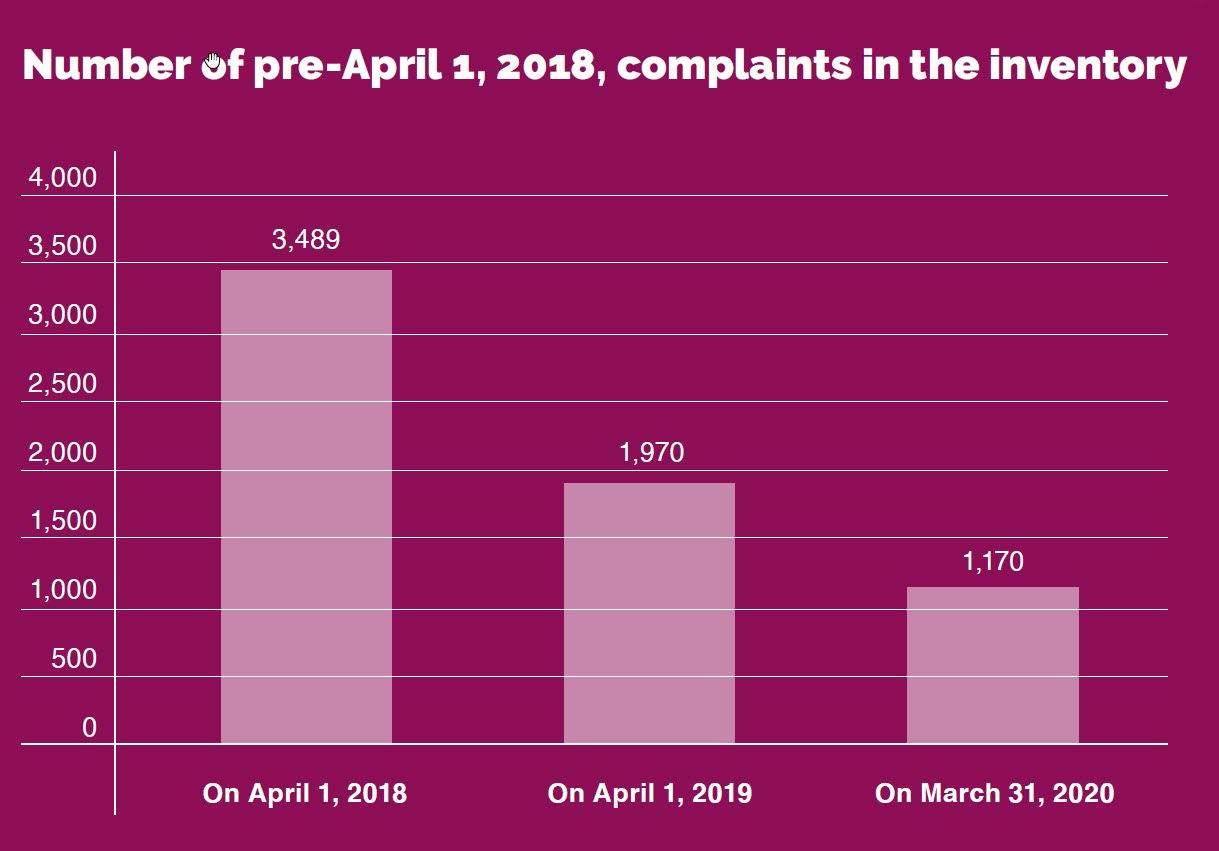

Nearly 800 of the complaints the OIC closed in 2019–20 dated from prior to April 1, 2018. The OIC has reduced the number of older files in the inventory by 66 percent over two years.

Closing older files has been a priority for the Commissioner since her appointment. The Commissioner has sought permanent funding to allow the OIC to augment its investigative capacity so it can respond to complaints more quickly. OIC staff also identified the 50 oldest files in its inventory and began dedicated efforts to close them in 2019–20.

Overall, the OIC closed a total of 5,528 files of all types in 2019–20. This meant that the OIC was able to keep the increase in its inventory of complaints to a minimum.

In March 2020, the OIC began to get a sense of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic would have on investigations. Institutions began to inform the OIC that, given their limited capacity for remote work, they might not be able to meet dates they had previously committed to for responding to complainants or the OIC.

Text version

Number of pre-April 1, 2018, complaints in the inventory

| On April 1, 2018 | On April 1, 2019 | On March 31, 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| 3,489 | 1,970 | 1,170 |

The big picture

6,173

Complaints registered

(↑ 150% from 2018–19)

5,528

Complaints closed

(↑ 112% from 2018–19)

3,559

Inventory files

(↑ 6% from 2018–19)

On the clock

Administrative complaints

Target to close?

90 days

Within target?

3,834 (89.7%) (2019–20)

866 (66.7%) (2018–19)

Median?**

48 days (2019–20)*

22 days (2018–19)**

Refusal complaints

Target to close?

270 days

Within target?

735 (58.7%) (2019–20)

779 (60.1%) (2018–19)

Median?**

180 days (2019–20)

191 days (2018–19)**

*Calculated for the 28 percent of administrative complaints not closed by the OIC Registry.

**From date of assignment to an investigator.

| Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well founded | Not founded | Resolved | Discontinued | ||||

| 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

| 724 (28%) | 597 (11%) | 499 (15%) | 344 (6%) | 983 (38%) | 4,057 (73%) | 501 (19%) | 530 (10%) |

Read more about OIC investigations in 2019–20

- Investigations involving the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Investigations involving the Canada Border Services Agency

- Classified records challenging for institutions and the OIC

- Solicitor-client privilege versus transparency

- Small groups may lead to the identification of individuals

- There’s more to a reasonable search than meets the eye

- The format of records can be as important as the content

Complaint activity, 2019–20

| Inventory | Closed in 2019-20 | Outcome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered before April 1, 2019 | Registered April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 | Total | Registered before April 1, 2019 | Registered April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 | Total | Well-founded | Not well-founded | Resolved | Discontinued | Total | |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 119 | 4,298 | 4,417 | 86 | 3,393 | 3,479 | 20 | 32 | 3,374 | 53 | 3,479 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 412 | 355 | 767 | 276 | 166 | 442 | 150 | 39 | 182 | 71 | 442 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 481 | 186 | 667 | 130 | 59 | 189 | 53 | 31 | 71 | 34 | 189 |

| National Defence | 155 | 209 | 364 | 67 | 78 | 145 | 30 | 15 | 52 | 48 | 145 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 133 | 136 | 269 | 73 | 49 | 122 | 36 | 10 | 52 | 24 | 122 |

| Privy Council Office | 189 | 61 | 250 | 41 | 7 | 48 | 26 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 48 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 188 | 54 | 242 | 85 | 8 | 93 | 23 | 8 | 18 | 44 | 93 |

| Library and Archives Canada | 143 | 89 | 232 | 33 | 8 | 41 | 28 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 41 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 112 | 75 | 187 | 48 | 39 | 87 | 14 | 12 | 22 | 39 | 87 |

| Health Canada | 131 | 52 | 183 | 90 | 9 | 99 | 23 | 6 | 16 | 54 | 99 |

| Parks Canada | 134 | 8 | 142 | 27 | 2 | 29 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 29 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 71 | 47 | 118 | 26 | 17 | 43 | 11 | 3 | 22 | 7 | 43 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 54 | 60 | 114 | 41 | 20 | 61 | 15 | 9 | 25 | 12 | 61 |

| Canadian Security Intelligence Service | 49 | 59 | 108 | 24 | 18 | 42 | 1 | 25 | 6 | 10 | 42 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 61 | 41 | 102 | 38 | 13 | 51 | 18 | 5 | 17 | 11 | 51 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 40 | 57 | 97 | 36 | 20 | 56 | 12 | 15 | 21 | 8 | 56 |

| Canada Post | 79 | 16 | 95 | 65 | 7 | 72 | 2 | 10 | 33 | 27 | 72 |

| Transport Canada | 58 | 34 | 92 | 23 | 13 | 36 | 11 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 36 |

| Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | 66 | 12 | 78 | 30 | 1 | 31 | 6 | 14 | 5 | 6 | 31 |

| Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 60 | 17 | 77 | 18 | 2 | 20 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 20 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 40 | 35 | 75 | 12 | 9 | 21 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 21 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 51 | 21 | 72 | 13 | 5 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 18 |

| Public Safety Canada | 43 | 21 | 64 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 27 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 49 | 2 | 51 | 15 | 2 | 17 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| Sub-total | 2,918 | 5,945 | 8,863 | 1,317 | 3,952 | 5,269 | 524 | 266 | 3,982 | 497 | 5,269 |

| Others institutions | 423 | 228 | 651 | 193 | 66 | 259 | 73 | 78 | 75 | 33 | 259 |

| Total | 3,341 | 6,173 | 9,514 | 1,510 | 4,018 | 5,528 | 597 | 344 | 4,057 | 530 | 5,528 |

Complaint activity, 2019-20

Inventory as of April 1, 2020

-

Complaints

as of April 1, 2019 -

New complaints

recieved ↑ 150% from previous year -

Complaints

closed ↑ 112% from previous year -

Complaints

as of March 31, 2020

Outcome

- Well founded

- Not well founded

- Resolved

- Discontinued

Investigations involving the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The OIC registered 355 complaints against the RCMP in 2019–20, ranking it second on the OIC’s list of the top institutions that were subject to complaints that year. Sixty-three percent of these complaints were about delays, continuing a pattern the OIC has noted for several years. This led the Commissioner to initiate a systemic investigation into the RCMP’s processing of access requests. The investigation will be completed in 2020–21.

Law enforcement exemption must be limited to legitimate investigations

Complaint investigations involving the RCMP often centre on information touching on very personal situations, including the interactions of members of the public with law enforcement agencies.

For example, the OIC completed an investigation in 2019–20 into the RCMP’s response to an access request that it could neither confirm nor deny the existence of records that listed the names and dates of anyone who had accessed the complainant’s file in the Canadian Police Information Centre’s (CPIC) database. The complainant, who had been criminally accused of assaulting an individual, was of the view that one of that individual’s relatives—a police officer (but not with the force that investigated the incident)—had unlawfully accessed his personal information in the CPIC.

The RCMP generally does not release information on ongoing investigations. Indeed, in its response to the access request, the RCMP said that if the requested records did exist, they would be exempted in their entirety because releasing them would have harmed an active investigation.

However, RCMP access officials subsequently acknowledged that the access to the complainant’s personal information in the CPIC was not part of a lawful investigation and that, therefore, the exemption did not apply. With the consent of the other police force, the RCMP released the records.

| Access requests* | Complaints | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 (% change) | 2018–19 | 2019–20 (% change) | |

| Received | 5,203 | 4,436 (–15%) | 256 | 355 (+39%) |

| Closed | 2,967 | 4,176 (+41%) | 165 | 442 (+168%) |

| Access requests closed in 30 days | Outcomes of complaint investigations | |||

| [Infographic] | 890 | 1,101 (+24%) |

|

|

*Most recent statistics available. Source: Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2018–19 annual report on access to information.

Firearm serial numbers are not personal information

In an October 2019 decision, the Federal Court ordered the RCMP to disclose 468 serial numbers of a particular type of firearm. The RCMP alleged that these numbers were personal information, but the Commissioner—and, eventually, the Federal Court—disagreed.

The decision is helpful in that it sets out guidance for determining whether there is a serious possibility that, if released, the information could identify an individual, as the definition of “personal information” requires.

After this decision was released, the RCMP also disclosed firearm serial numbers related to a separate Federal Court case.

See also, “Small groups may lead to the identification of individuals.”

Long-gun registry details see the light of day

Bill C-71 (An Act to amend certain Acts and Regulations in relation to firearms), which became law in June 2019, restored the right of access to the records in the federal long-gun registry. The right of access was the subject of a systemic investigation in 2015.

A former Information Commissioner had challenged in the Ontario Superior Court the constitutionality of the federal government’s elimination of the right of access to these records. With Bill C-71’s coming into effect, the current Commissioner was able to discontinue this action, since it had become moot.

The Commissioner’s Federal Court application against the RCMP was then able to resume. The RCMP processed most of the fields of information at issue in the litigation under the Access to Information Act, as the application sought. Ultimately, the RCMP disclosed most of the information that it processed, with the remaining information withheld under the exemption for personal information. The litigation was, therefore, settled.

Seeking to release information on compassionate grounds exposes shortcomings in the law

The OIC completed a number of investigations resulting from complaints from individuals seeking information about RCMP inquiries into the deaths of family members. The complainants were concerned because the RCMP had withheld information they had asked for so they could get a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding the deaths.

The RCMP had protected the information under parts of section 16 (law enforcement and investigations). The Commissioner determined that the information met the requirements of the exemption and was also satisfied that the RCMP had reasonably exercised its discretion to decide to withhold the information. Among the factors the RCMP considered was that the Privacy Act protects the personal information of deceased individuals for 20 years after their death.

These investigations, however, highlight shortcomings in the interplay between the Privacy Act and Access to Information Act that limit the ability of institutions to release information about a deceased individual to a spouse or other close relative on compassionate grounds, as is possible in several provinces.

In a September 2019 submission to the Department of Justice Canada’s review of the Privacy Act, the Commissioner recommended that the sections in both that law and the Access to Information Act that deal with personal information be amended accordingly.

Investigations involving the Canada Border Services Agency

The OIC registered 136 complaints about the handling of access requests by Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) in 2019–20, ranking it fifth on the OIC’s list of the top institutions that were subject to complaints that year.

Searching backup tapes not always necessary

A complainant told the OIC that CBSA had not provided all the documents he had asked for because he did not receive any deleted emails, which he had specifically requested. He also wanted information from backup tapes.

During the investigation, the OIC and CBSA discussed both concerns. CBSA officials confirmed that they had searched the relevant folder for deleted emails and had found no responsive records.

With regard to the backup tapes, while the Act requires institutions to make every reasonable effort to assist requesters, searching backup tapes is not required as a matter of course. However, such a search might be warranted when, for example, tapes contain what might be the only copy of records that fall within the scope of an access request—when the records were knowingly or accidentally deleted. Similarly, a search would be necessary in order to comply with a court order or as part of disaster recovery. None of these circumstances applied in this instance. The Commissioner concluded that CBSA had conducted a reasonable search for records in response to the access request.

Automatically generated numbers are not “customs information”

When responding to a request for information related to tariffs on fishing vessels and various vessels for processing or preserving fishery products, CBSA withheld information under subsection 24(1) (disclosure restricted by another law). This provision requires institutions to withhold information when a provision in another piece of legislation—in this case, the Customs Act—restricts its disclosure.

In particular, the complainant was concerned that CBSA had refused to release the file numbers associated with entries in its Technical Reference System, in which CBSA records precedent-setting decisions on tariff classification and also tracks cases. The OIC was of the view that these numbers were not actually “customs information” obtained or prepared by CBSA, and therefore their disclosure was not restricted by the relevant provision of the Customs Act.

The OIC sought written representations from CBSA on its position, at which point CBSA access officials reviewed the matter and agreed to release the numbers to the complainant.

| Access requests* | Complaints | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 (% change) | 2018–19 | 2019–20 (% change) | |

| Received | 7,466 | 7,673 (+3%) | 298 | 136 (–54%) |

| Closed | 7,219 | 8,073 (+12%) | 165 | 122 (–26%) |

| Access requests closed in 30 days | Outcomes of complaint investigations | |||

| [Infographic] | 4,027 | 4,732 (+18%) |

|

|

*Most recent statistics available. Source: Canada Border Services Agency 2018–19 annual report on access to information.

Previously disclosed information would cause greater risk of harm today

When responding to a request for seizure statistics, CBSA withheld the locations of the specific ports of entry under paragraph 16(1)(c) (law enforcement). This provision allows institutions to withhold information, the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the enforcement of any law of Canada—in this case, the Customs Act.

The complainant was concerned that CBSA had previously disclosed this same information in a response to a similar access request submitted in 2013. The OIC sought written representations from CBSA to understand why the type of information that was previously released would now be injurious to the enforcement of the Customs Act.

Although CBSA acknowledged in its representations that it had released this information in the past, it was able to show that there was a greater potential for the information to be used to circumvent the Customs Act in 2019, particularly for smuggling-related purposes. The Commissioner was satisfied, based on the information received, that the exemption was properly applied and that CBSA had appropriately exercised its discretion to withhold the information.

Classified records challenging for institutions and the OIC

Processing access requests and investigating complaints involving Secret and Top Secret records— information that, if compromised, could injure the national interest—presents challenges both for institutions and for the OIC. Institutions need adequate digital infrastructure and processes in place. This increases institutions’ personnel, information technology and information management security requirements. It also makes it difficult for the institutions processing the requests to seek the advice of other institutions on the application of exemptions and to share working copies of the records with the OIC during complaint investigations. In all cases, institutions and the OIC must tightly safeguard highly classified information.

In early 2020, almost 20 percent of the complaints in the OIC’s inventory related to access requests for national security-related information. Of these, investigations into whether institutions conducted reasonable searches for records or into the application of exemptions involved about 45,000 pages of classified information. However, access requests for records associated with delay and time extension complaints could involve additional millions of pages of classified documents. In short, investigating these files is an immense task.

The Commissioner received permission from the President of the Treasury Board to increase the number of investigators with special delegation to examine institutions’ application of exemptions to records associated with international affairs, national security and defence. This means the OIC can more promptly begin these complex investigations. Complaints requiring special delegation to investigate accounted for 8 percent of all complaints about the application of exemptions in 2019–20.

In September 2019, the Commissioner met with senior officials from the Privy Council Office, including the Prime Minister’s then national security and intelligence advisor, regarding that institution’s substantial inventory of national security and intelligence-related complaints involving mainly historic records to develop specific strategies for dealing with them effectively.

However, a more fundamental fix is also called for—establishing a declassification system. The OIC published a declassification strategy for national security and intelligence records in February 2020 that includes 15 recommendations.

With a proper system of declassification and review of historical national security and intelligence-related records, many of the records associated with access requests and complaints could have been declassified and sent to Library and Archives Canada (LAC), and could now be more readily accessible to researchers and others who seek access to them. But, in the absence of such a declassification regime, they remain at the original institution, inaccessible except through an access system ill suited to this specific purpose.

Even when records are transferred to LAC, investigating complaints is challenging when the information remains classified. Such was the case with an investigation completed in 2019–20 involving the RCMP Security Service file on René Lévesque, which comprised some 2,750 pages of records, all classified Top Secret. While the OIC was able to secure three supplementary releases of information since LAC originally responded to the request (totalling close to 85 percent of the withheld information), it took nearly 15 years to do so and numerous consultations between LAC and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). Although the latter was cooperative with both LAC and the OIC, CSIS’s involvement and the time and effort required (not least because of the need for personnel with Top Secret security clearance, along with special storage, secure computers and secure transmission of material) would have been reduced if these records, which date back 50 years or more, had been declassified.

“Protected” designation for some information does not protect it all from disclosure

A related issue arises when institutions decide to broadly rely on the designation of records as “Protected” to withhold information rather than looking at whether the information qualifies for exemption under a specific provision.

For example, Global Affairs Canada withheld requested export permits in their entirety under various parts of subsection 20(1) (confidential third-party information). In justifying the use of paragraph 20(1)(b) (confidential third-party financial, commercial, scientific or technical information), access officials told the OIC that because the system used to store and process applications for export permits was rated for records designated up to Protected B, the records must have been communicated with a reasonable expectation of confidence that they would not be disclosed.

The Commissioner was not persuaded by this argument, noting that a document’s security designation does not establish that all the information it contains originated and was communicated with a reasonable expectation that it would not be disclosed. Global Affairs’ position was further undermined by the fact that its predecessor, the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, had previously released the types of information at the centre of the complaint. The investigation resulted in additional information being disclosed to the complainant.

Solicitor-client privilege versus transparency

Under section 23, institutions may withhold information protected by solicitor-client privilege. This exemption was cited in nearly 16 percent of the complaints about institutions’ refusing access to requested records the OIC received in 2019–20.

Releasing legal hours worked is in the public interest

One notable investigation related to the application of section 23 the OIC completed in 2019–20 involved the names of employees and external counsel who had worked on two public inquests into the high-profile 2007 suicide of an individual in custody, along with the hours the employees and external counsel had worked and the cost of their services.

Legal billing is often the subject of investigations. Rates, hours worked and the names of counsel are presumed to be subject to solicitor-client privilege; however, it can be difficult to determine when that presumption can be put aside and the information released.

The Department of Justice Canada had disclosed the total amount of legal fees incurred. In urging the institution to disclose additional information during the investigation, the Commissioner underlined the government’s commitment to openness and setting a higher bar for transparency.

At the conclusion of the investigation, the Commissioner was of the view that the Minister of Justice should have considered the public interest more thoroughly when exercising his discretion to decide whether to release the information withheld under section 23, and recommended that he re-exercise his discretion. The Minister did so but ultimately decided to withhold the names and costs associated with the individuals who had been involved in the inquests.

However, the Minister did agree to release the sub-total of hours the various individuals worked, highlighting the importance of institutions’ considering all the factors for and against disclosure when making decisions on access.

Court decision clarifies aspects of discretion under solicitor-client privilege exemption

In a decision released in April 2019, the Federal Court of Appeal clarified provisions of the Access to Information Act.

The access request at the centre of the case was submitted to the Privy Council Office for information relating to four senators. The Court found that most of the requested information was subject to exemptions.

In addition, the Court clarified the extent of the “continuum of communications” protected by solicitor-client privilege and what constitutes a reasonable exercise of discretion. With regard to the latter, the Court noted that institutions must take relevant factors into account but are not required to explain in detail how they weighed every factor against every other.

The Court’s ruling also clarified the scope of the exception to the definition of “personal information” for discretionary benefits of a financial nature.

Small groups may lead to the indentification of individuals

Information institutions withhold under section 19 (personal information) must meet the definition of “personal information” in section 3 of the Privacy Act. A key aspect of that definition is that the information must be about an “identifiable” individual. By extension, this definition applies to small groups of people, from which an individual might reasonably be identified.

Members of groups of five or less could be identified if equity data were released

In one instance, the members of the small group were the holders of the position of Canada Research Chair in universities across the country. The complainant had asked the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) for statistics on the number of individuals from the four employment equity groups (women, Indigenous peoples, visible minorities and individuals with disabilities) in this role. SSHRC withheld information citing a number of exemptions. Over the course of the investigation, the institution reconsidered its position in some regards, but continued to protect information under subsection 19(1).

The Commissioner agreed with this position when the data involved a group of five people or less, as was the case for individuals who had self-identified as being Indigenous people or as having a disability. Disclosing the small number of people in these small groups would raise a serious possibility that the individuals could be identified.

The Commissioner was also satisfied that SSHRC had reasonably concluded that the personal information did not warrant being disclosed under subsection 19(2).

What size of group may render its members “identifiable

In three investigation files, involving sub-areas of various postal codes across Canada, Health Canada refused to disclose the first three characters of postal codes (which are called “forward sortation areas”). Instead, Health Canada only disclosed the first character of each of the postal codes, claiming that the second and third characters constituted personal information that could not reasonably be severed and disclosed.

The postal codes in question were those of 11,842 registered users of medical cannabis, 712 designated or personal producers, and 575 designated or personal producers who were authorized to produce and/or to store large amounts of medical cannabis.

The first two investigations only involved the first three characters of postal codes. The third involved full addresses of designated or personal producers, much of which the Commissioner accepted as constituting personal information (e.g. street names and numbers, and the last three digits of postal codes) because it is about identifiable individuals. However, the third investigation also involved forward sortation areas and city names.

The Commissioner was of the opinion that the populations of most forward sortation areas and cities are too large to be about identifiable individuals, and that Health Canada provided no concrete evidence to the contrary. Accordingly, she found this information not to be personal information and was of the view that Health Canada was required to disclose most forward sortation areas and cities, since they could reasonably be severed from any personal information in the records at issue.

The Commissioner made a recommendation to that end, but Health Canada declined to follow it. The Commissioner recently filed applications in the Federal Court on behalf of the complainants.

Court decision clarifies rules for transferring access requests

In an April 2019 decision, the Federal Court of Appeal defined the scope of the provision in the Access to Information Act (section 8) that allows one institution to transfer an access request to another institution. The Court found that section 8 does not require an institution to have control of records responsive to a request in order to be able to transfer the request to a second institution. The second institution must, however, have a greater interest in a requested record, and must consent to the transfer, in addition to the other requirements for a valid transfer set out in section 8. This section promotes efficiency in the access system, since the requester does not have to make the same request to the second institution.

There’s more to a reasonable search than meets the eye

Among the responsibilities institutions have when responding to access requests is to carry out a reasonable search for records. A number of factors can affect whether an institution’s search is reasonable.

A second search, specifically defined, located responsive records

One complaint centred on the fact that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) had been unable to locate any records containing the number of males identifying as transgender housed in women’s correctional facilities, and their convictions.

During the investigation, the OIC learned that CSC does track gender considerations and gender fluidity but nothing as specific as males identifying as transgender who are housed in women’s correctional facilities. This likely explains why no records were found during the first search. The OIC pressed CSC to conduct a second search. In doing so, CSC found and then released a one-page document that contained the details the complainant sought.

Sometimes searching for records in the possession of another party is necessary

A second investigation centred on whether Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) should have searched for records it did not have possession of but did have control over due to a contractual arrangement with a third party.

During the investigation, the OIC reviewed how NRCan had processed the access request and examined the records to identify any irregularities in what NRCan disclosed. In doing so, the OIC came to the view that NRCan might have had control of a number of additional records that were in the possession of the third party.

Despite disagreeing with the basis for the Commissioner’s recommendation to ask the third party for responsive records, NRCan followed the recommendation. However, in the end NRCan confirmed that the third party did not have any responsive records.

The format of records can be as important as the content

Government institutions have an obligation to make every reasonable effort to provide records in response to access requests in the format requested. Individuals can have any number of reasons for asking for records in a particular format—from how they wish to use the information to whether they have Internet access.

In one investigation closed in 2019–20, the complainant had sought records in a particular format in order to shed light on whether a First Nations band council election had been conducted fairly. In particular, the complainant wished to receive colour copies of seven contested ballots so he could see the colour of the marks on them and determine whether those marks had been made fraudulently.

Access officials at Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) told the OIC that they could not produce the contested ballots in colour because they had to process all records to be released using the institution’s redaction software, which converted material to black and white.

The OIC informed CIRNAC that relying on this technicality as a reason for failing to produce the document in the format requested did not fulfill its duty to make every reasonable effort to provide records in the format requested. The OIC suggested other methods to process the document in colour, such as marking colour copies with a stamp to show that they had been disclosed. Ultimately, CIRNAC produced a colour version of the contested ballot that was of greatest importance to the complainant.