2014-2015 2. Investigations

The Information Commissioner is the first level of independent review of government decisions relating to requests for access to public-sector information. The Access to Information Act requires the Commissioner to investigate all the complaints she receives.

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner received 1,738 complaints and closed 1,605. The difference in the total number of complaints closed as compared to 2013–2014 is due to two reasons. First, there were a number of complex investigations in 2014–2015 (as described in Chapter 1) that required the dedicated attention of a number of investigators. Second, there was a reduction in financial resources available.

The overall median turnaround time from the date a file was assigned to an investigator to completion was 83 days.

At the end of the fiscal year, the Commissioner’s inventory of complaints was 2,234 files.

Appendix A contains more statistical information related to the complaints the Commissioner received and closed in 2014–2015.

Summary of caseload, 2010–2011 to 2014–2015

| 2010–2011 |

2011–2012 |

2012–2013 |

2013–2014 |

2014–2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Complaints carried over from previous year |

2,086 |

1,853 |

1,823 |

1,798 |

2,090 |

New complaints received |

1,810 |

1,460 |

1,579 |

2,069 |

1,738 |

New Commissioner-initiated complaintsFootnote 1 |

18 |

5 |

17 |

12 |

11 |

Total new complaints |

1,828 |

1,465 |

1,596 |

2,081 |

1,749 |

Complaints discontinued during the year |

692 |

641 |

399 |

551 |

416 |

Complaints settled during the year |

18 |

34 |

172 |

193 |

276 |

Complaints completed during the year with finding |

1,351 |

820 |

1,050 |

1,045 |

913 |

Total complaints closed during the year |

2,061 |

1,495 |

1,621 |

1,789 |

1,605 |

Total inventory at year-end |

1,853 |

1,823 |

1,798 |

2,090 |

2,234 |

Mediation

Text Version

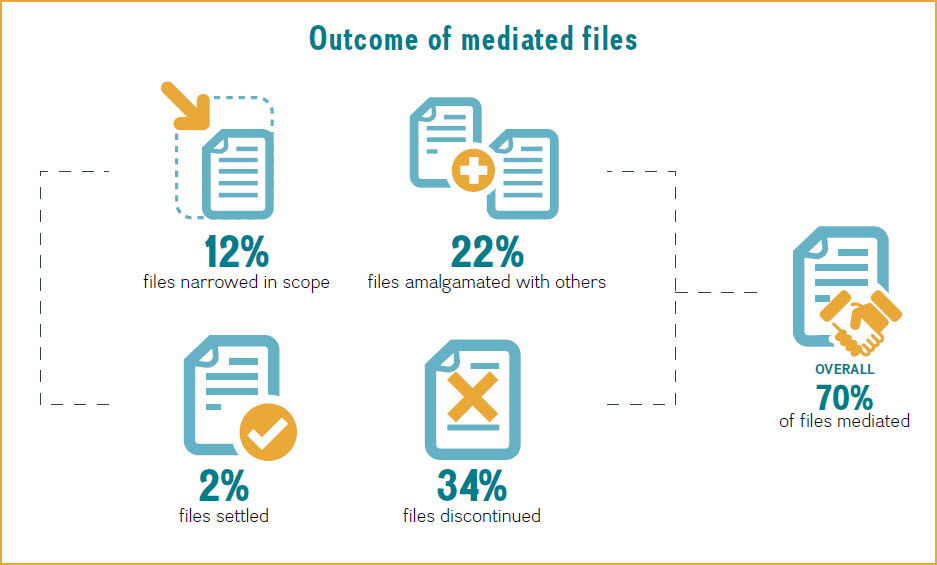

This infographic shows the outcome of mediated files in the 2014–2015 mediation pilot project.

Overall, 70% of files chosen for this project were mediated to one of the following outcomes:

12% of files were narrowed in scope

22% of files were amalgamated with others

2% of files were settled

34% of files were discontinued

The Commissioner conducted a mediation pilot project in 2014–2015 to resolve certain complaints more quickly, without the need for full investigations.

Of the 318 files chosen for the project, 70 percent were mediated to one of the following outcomes:

- scope narrowed;

- amalgamated with other similar files;

- settled by agreement of the parties; or

- discontinued.

An example of the scope of a file being narrowed occurred when a complaint against Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada that originally involved roughly 11,500 pages was narrowed to 500 following discussions with the complainant. In another file, against Industry Canada, approximately 4,700 pages were narrowed to 10. Narrowing the scope of files allows the investigator to focus on the records that are of greatest importance to the complainant and often results in files being completed more quickly. It also reduces the workload for institutions and the Commissioner.

When the Commissioner amalgamates files, it is usually because a single complainant has a number of complaints against one institution, often on the same or similar subject matters. Joining the files together makes it possible for the Commissioner to determine what information is the most important to the complainant and to work on those priorities, thus increasing efficiency. For example, the Commissioner amalgamated 25 files against the Canada Revenue Agency and was able to settle them all at once.

When matters are settled, the institution and complainant agree to close the file without a full investigation. For example, a meeting between representatives of the Commissioner and Bank of Canada officials, plus correspondence between the Office of the Information Commissioner and both the institution and the complainant, led the Bank to agree to fully disclose records about a complaint of alleged employee misconduct. In another instance, a complainant agreed to settle a complaint against Citizenship and Immigration Canada after being given the opportunity to confirm that the document the institution proposed to release was the document he sought.

A complaint may be discontinued at any time, either as a result of mediation efforts or during an investigation. For example, when mediating a complaint against National Defence, an investigator found that some records a complainant sought were available from the courts. The complainant obtained the records and the complaint was discontinued. In another instance, the Commissioner determined that she had previously dealt with a complaint similar to one against the Bank of Canada, which had resulted in the release of additional records. These records were sufficient for the complainant, who then discontinued the complaint.

Timely access: A basic obligation under the Act

In the era of social media and the 24-hour news cycle, requesters expect a constant stream of information at their fingertips. However, responses to access requests often do not live up to that expectation.

In the spring of 2015, for example, the response to a parliamentary written question showed that many institutions had active requests dating back several years, with the oldest originating in January 2009. In addition, the responses to 58 percent of the 251 requests reported were overdue, even though institutions had claimed lengthy time extensions in some instances.

Timeliness of responses to access requests eroding

The most recent annual statistics from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat suggest that timely access to government information is still out of reach in many regards (figures from 2013–2014):

- Fewer requests completed in 30 days. The proportion of requests institutions completed in 30 days in 2013–2014 dropped to 61 percent, from 65 percent in 2012–2013.

- More request responses late. The proportion of all requests institutions answered after the deadline grew to 14 percent, up from 11 percent in 2012–2013.

Longer time extensions to respond to requests. Between 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, the proportion of all time extensions of more than 120 days climbed from 13 percent to 19 percent. Over the same period, the proportion of extensions for 30 days or less dropped from 34 percent to 21 percent.

The use of long extensions or failing to meet deadlines indicates that institutions are not fulfilling one of their most basic duties under the Act, that of timely access.

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner registered 569 delay-related complaints against 47 institutions. Delay complaints are either about institutions missing the deadline for responding to requests or about the time extensions they take to process requests.

The following are noteworthy investigations related to timeliness that the Commissioner completed in 2014–2015.

Parks Canada

The Commissioner investigated why Parks Canada had missed its March 2014 deadline to respond to a request for information about Parks Canada’s purchase of an Ontario property. Through her investigation, the Commissioner learned that the delay had been caused in part by the subject-matter expert within Parks Canada, who had sent the requested records to the access office for processing one month after the response to the requester was due. The file had also lain dormant in the access office at various times.

During the investigation, the Commissioner asked Parks Canada on more than one occasion to commit to a date to respond to the requester. Each time, the Commissioner found the proposed timeframe to be too long, with too much time set aside for various steps in the response process, including taking 11 weeks for internal approvals. After the Commissioner gave the institution’s chief executive officer her recommendations to release the records, the institution committed to releasing the requested records in January 2015.

In light of this complaint and others like it, the Commissioner launched a systemic investigation in the winter of 2015 to examine Parks Canada’s approach to processing access requests.

Delays responding to the Parliamentary Budget Officer

Delays in the response process also became evident during three investigations of complaints made by the Parliamentary Budget Officer. The Parliamentary Budget Officer provides independent analysis of the nation’s finances, the government’s estimates and trends in the Canadian economy. He complained to the Commissioner about delays in receiving information from various institutions about the possible impact fiscal restraint measures announced in Budget 2012 might have on their service levels.

Access delayed is access denied

In her special report to Parliament on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner made a number of recommendations to amend the Access to Information Act to promote timeliness:

- limit time extensions for responding to requests to 60 days, and require the Commissioner’s permission to take longer ones;

- allow extensions, with the Commissioner’s permission, when institutions receive multiple requests from one requester within 30 days;

- replace the exemption for information about to be published with an extension covering the publication period and require the institution to release the information if it is not published when the extension expires; and

- give the Commissioner the power to order institutions to release records to requesters.

The Parliamentary Budget Officer had originally asked deputy ministers for this information outside the access to information regime in April 2012. Having received few responses to his queries, he sought the same information through formal access to information requests in the summer of 2013. However, several institutions, including Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Environment Canada, did not meet their deadlines for responding.

Through her investigations, the Commissioner found that a number of circumstances had led to the delays. Indeed, these three files featured several of the common problems that result in delays: files not advancing in the access office, unnecessarily long time extensions taken for consultations on a small number of pages, and multiple consultations taken consecutively rather than concurrently.

To resolve the complaints, the Commissioner asked the three institutions for a work plan and commitment date for responding to the requester. Fisheries and Oceans Canada provided a response in February 2015, and the RCMP and Environment Canada in March 2015.

Counteracting the culture of delay

Counteracting the culture of delay that leads to complaints about timeliness requires senior officials in institutions—up to and including deputy ministers and ministers—to exercise consistent and continuous leadership. The Commissioner made a number of timeliness-related recommendations in her special report on modernizing the Act that are intended to bring discipline to the Act with regard to response times (see box, “Access delayed is access denied”). The Federal Court of Appeal’s decision in Information Commissioner of Canada v. Minister of National Defence, 2015 FCA 56, is also expected to instill more discipline in the process of taking and justifying time extensions (see “The culture of delay”). The Commissioner will issue an advisory notice in 2015–2016 on how she will implement the Court of Appeal’s decision when conducting investigations.

Maximizing disclosure for transparency and accountability

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized that the “overarching purpose” of the Access to Information Act is to facilitate democracy (see Dagg v. Canada (Minister of Finance), [1997] 2 SCR 403 at para. 61). Having access to information held by government institutions helps ensure citizens can participate meaningfully in the democratic process and also increases government accountability.

“The public is prevented from holding its government to account under the current regime. And it’s not necessarily the fault of people who administer the system—the people who work and process your access requests—but the law is very heavily tilted in favour of protecting government information.”

—Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault, speaking to Carleton University students during Right to Know Week, 2014

However, the right of access is not absolute. The Act stipulates that the general right of access may be restricted when necessary by limited and specific exceptions.

The Commissioner has come to the conclusion that the current exceptions to the right of access do not strike the right balance between the public’s right to know and the government’s need to protect limited and specific information. Broad exemptions and exclusions in the Act allow more information to be withheld than is necessary to protect the interests at stake.

This conclusion is supported by disclosure rates across the government. There has been a significant drop in the percentage of requests for which institutions release all information over the years.

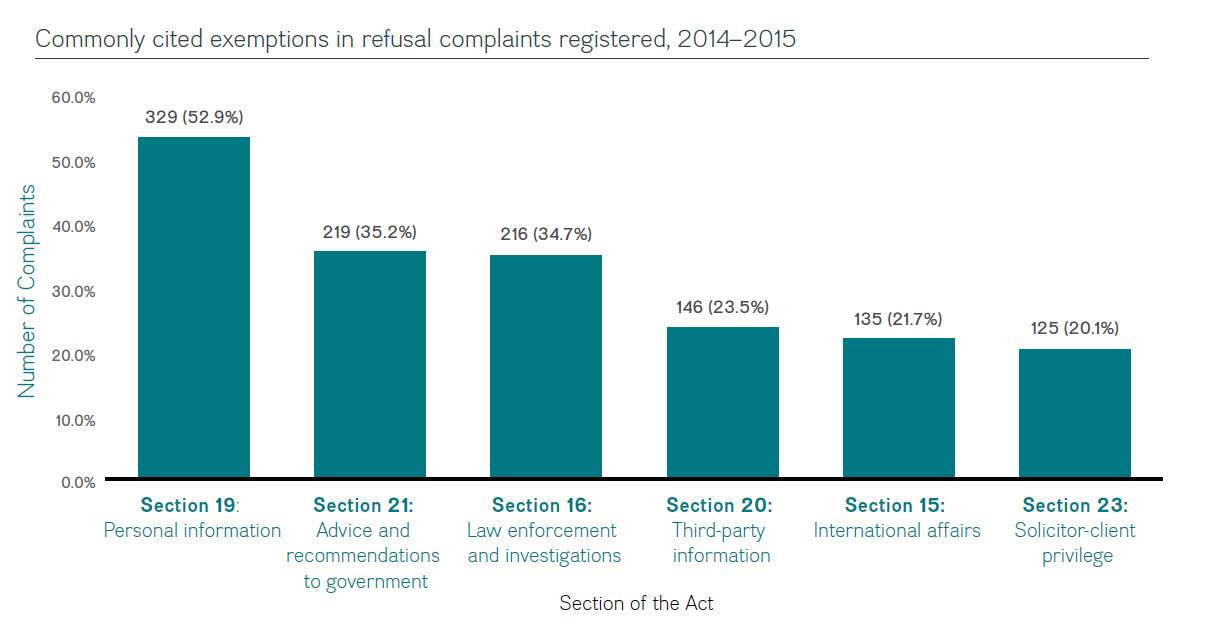

The graph below sets out the most common exemptions cited in complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015.

Commonly cited exemptions in refusal complaints registered, 2014–2015

Note: The sum of all percentages may exceed 100 percent, because a single complaint may involve multiple exemptions.

Text Version

The vertical bar chart represents the exemptions that were cited the most frequently cited in the refusal complaints registered in 2014–2015. The X-axis refers to the exemptions under the section of the Act while the Y-axis represents the number of refusal complaints for which the exemptions was cited, as a proportion of the total refusal complaints registered.

The results are as follows:

- Personal information (Section 19): 329 complaints (or 52.9% of all refusal complaints registered) evoked this exemption;

- Advice and recommendations to government (Section 21): 219 complaints (or 35.2%) evoked this exemption;

- Law enforcement and investigations (Section 16): 216 complaints (or 34.7%) evoked this exemption;

- Third-party information (Section 20): 146 complaints (or 23.5%) evoked this exemption;

- International affairs (Section 15): 135 complaints (or 21.7%) evoked this exemption;

- Solicitor-client privilege (Section 23): 125 complaints (or 20.1%) evoked this exemption.

Section 19 (Personal information)

Section 19, which is a mandatory exemption for personal information, is by far the most cited exemption by institutions when they respond to access requests. Institutions invoked it more than 20,000 times in 2013–2014. More than half (53 percent) of the refusal complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015 (329 complaints) involved section 19.

Bringing section 19 up to date

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner made the following recommendations related to section 19:

- require institutions to seek the consent of individuals to whom personal information relates, whenever it is reasonable to do so, and require institutions to disclose that information once consent is given;

- allow institutions to disclose personal information to the spouse or relatives of deceased individuals on compassionate grounds;

- allow personal information to be disclosed when there would be no unjustified invasion of privacy; and

- exclude workplace contact information for non-government employees from the definition of “personal information.”

The Privacy Act defines “personal information” as “information about an identifiable individual that is recorded in any form.” This definition is incorporated into the Access to Information Act by reference.

Section 19 contains a number of circumstances that allow institutions to release personal information that they would otherwise have to withhold. These circumstances include that the person to whom the information relates consents to its release or that the information is publicly available.

Applying section 19 too broadly

While acknowledging that the exemption is mandatory, the Commissioner has found that institutions apply it too broadly in many instances.

A notable example of this in 2014–2015 related to a request for records about the seizure by RCMP officers of improperly stored firearms from homes affected by the 2013 flood in High River, Alberta. Citing section 19, the RCMP withheld information that identified where in each residence the weapon had been recovered. The descriptions of the locations ranged from the vague (“in residence”) to the more specific (“closet of master bedroom” and “under the bed in the bedroom”). The RCMP argued that releasing such information could make it possible to identify the homeowners. The Commissioner did not agree with the RCMP. As a result of the Commissioner’s investigation, the RCMP released the information.

Seeking consent

Section 19 allows institutions to release personal information when the person to whom it relates consents to its disclosure. However, the Act is silent as to when an institution should seek the consent of an individual. While some individuals refuse to grant consent when asked, others agree, which often results in more information being released to the requester. During two investigations closed in 2014–2015, the Commissioner recommended that institutions seek consent from individuals to release their personal information. In the first instance National Defence asked eight individuals to release their names and scores on a job competition. These individuals declined. In contrast, 10 people involved in meetings with the Department of Finance Canada related to possible changes to the Income Tax Act did consent to having their personal information released, and additional information was disclosed to the requester.

Releasing information on compassionate grounds

The Commissioner often receives complaints from relatives who are seeking information about the death of a loved one. A common reason they complain to the Commissioner is that an institution withholds information under section 19. In these situations, the Commissioner frequently recommends that the institution consider releasing the information on compassionate grounds, when doing so would be in the public interest and would clearly outweigh the invasion of privacy of the deceased. As a result of an investigation into a complaint about the RCMP’s refusing access to information related to a workplace accident that resulted in a death, the Commissioner made this recommendation. The RCMP consulted the Office of the Privacy Commissioner on the matter. The requester, a relative of the deceased, subsequently received additional records from the RCMP.

Publicly available information

Work-related contact information of non-government employees is personal information and is therefore protected from disclosure by section 19 (Information Commissioner of Canada v. Minister of Natural Resources, 2014 FC 917; see “The scope of personal information”).

One complaint about Health Canada’s refusal to release work-related contact information of non-government employees centred on the names and contact information of participants in a study on the possible health effects of wind turbines. The institution argued that some participants were not government employees and that, therefore, their personal information had to be protected. However, subsection 19(2) allows for the release of personal information when it is already publicly available. The investigator found that much of the information at issue was on Health Canada’s website, although the institution said that it was not at the time of the request. Health Canada subsequently released the information in question to the requester.

Section 21 (Advice and recommendations to government)

This provision exempts from disclosure a wide range of information relating to policy- and decision-making. There is a public interest in protecting such information to ensure officials may provide full, free and frank advice to the government. There is also a public interest in releasing this kind of information so citizens may get the information they need to be engaged in democracy and hold the government to account.

Institutions invoked this exemption nearly 10,000 times in 2013–2014. More than one third (35 percent) of the refusal complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015 (219 files) involved section 21.

In her investigations, the Commissioner often finds that institutions have applied section 21 too broadly and are unable to show how the information falls within one of the various classes of information the exemption is designed to protect.

Narrowing section 21

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended the following to narrow the scope of section 21:

- extend the list of specific examples of information to which section 21 does not apply to include factual materials, public opinion polls, statistical surveys, appraisals, economic forecasts, and instructions or guidelines for employees of a public institution;

- reduce the time the exemption applies from 20 years to five years or once the decision to which the advice relates has been made, whichever comes first; and

- add a “reasonable expectation of injury test.”

In her report, the Commissioner also recommended that there be a general override for all exemptions to ensure that institutions take the public interest in disclosure into account when considering whether to apply any of the exemptions within the Act. Institutions should be specifically required to consider factors such as open government objectives; environmental, health or public safety implications; and whether the information reveals human rights abuses or would safeguard the right to life, liberty or security of the person. Given the type of information covered by section 21, this override would be particularly useful in helping maximize disclosure and fostering transparency and accountability.

Partisan letters on a website

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD) cited section 21 when it withheld large portions of communications and briefing materials about the posting of partisan letters on the former Canadian International Development Agency’s website. The requester noted in her complaint that she had made similar requests in the past but had never seen the records treated in this manner before.

The Commissioner’s investigation found that some of the withheld information did not qualify for the section 21 exemption. For example, DFATD had exempted factual information, which does not fall within the parameters of section 21. In addition, DFATD had redacted some details in certain places but released the same information in others. In response to the Commissioner’s recommendations, DFATD provided more information to the requester.

Defunding the Canadian Environmental Network

Environment Canada exempted under section 21 large portions of a briefing note to the Minister of the Environment about whether to continue funding the Canadian Environmental Network. The requester complained to the Commissioner about this response. The institution argued that most of the information in the briefing note was advice and recommendations to the Minister. Through her investigation, however, the Commissioner found that not all the information qualified for the exemption and recommended the institution complete a detailed review of the records. Following this recommendation, Environment Canada reconsidered its use of section 21 and in some instances exercised its discretion to release additional information. This resulted in the institution withholding only the minimum amount of information that specifically required protection. The additional information released included background, contextual material related to the decision, headings and references to attachments.

Funding of programs related to violence against Aboriginal women

A requester asked the Department of Justice Canada for information regarding violence against Aboriginal women that was created during a specific time period. In its response, the institution withheld under section 21 information on approval documents and applications for funding under two programs related to violence against Aboriginal women. Through her investigation, the Commissioner found that the institution had broadly applied section 21. The Commissioner concluded that much of the withheld information did not meet the requirements for the exemption and asked the institution to reconsider its position. In response, the institution abandoned the application of section 21 in some instances. In others, the institution took into account the passage of time and the fact that the funding decision had been made and decided to exercise its discretion to release more information. In the end, all but limited and specific information was released.

An additional positive outcome of the investigation was that the institution changed its approach to processing access requests related to grants and contributions records. The institution also said it would amend a paragraph of the Conditions section of the application form for these programs to indicate that in the event of an access request, the information in the application would be disclosed, except for personal information.

Section 16 (Law enforcement and investigations)

Narrowing the scope of section 16

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner noted that paragraph 16(1)(c), which exempts information the disclosure of which could harm law enforcement activities and investigations, is sufficient to balance the protection of law enforcement-related information with the right of access. In light of this, she recommended that other paragraphs under section 16—related to techniques for specific types of investigation, for example—be repealed.

This provision protects information related to law enforcement. Section 16 covers the work of a wide range of federal bodies, including the RCMP, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and the Canada Revenue Agency.

Institutions invoked section 16 more than 7,900 times in 2013–2014. Section 16 was the subject of 35 percent of the refusal complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015 (216 files).

There is a public interest in both protecting information under this provision, to ensure law enforcement activities can progress unimpeded, as well as ensuring that information is released such that Canadians can hold law enforcement bodies to account.

Political activities of registered charities

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner investigated a complaint against the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) related to letters it had sent to registered charities reminding them of the limits they must respect with regard to their political activities. In response to an access request, CRA had refused to release a two-page document containing instructions for preparing these letters, saying that disclosing the instructions would prejudice future enforcement of the Income Tax Act. The Commissioner questioned CRA about its use of section 16 for procedural information of this type and found that the institution could not substantiate the harm that could occur if the documents were disclosed. CRA subsequently released the two pages to the requester.

Prejudicing an investigation that is closed

Institutions often cite section 16 in order to withhold information so as not to prejudice ongoing investigations. The Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) took this approach and withheld an entire investigation file in response to a request, without considering whether any information could be severed and the rest released. During the investigation into the resulting complaint, the Commissioner learned that the institution had refused to release the file, despite the fact that the matter was concluded, although not officially closed in the case management system. The Commissioner questioned how releasing the requested records could prejudice an ongoing investigation when the one at issue was essentially complete. Although the requester did receive the records, it was only as the result of a second request he made at the suggestion of the CHRC.

Section 20 (Third-party information)

Striking the right balance with section 20

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended that section 20 contain a two-part test. The test would allow third-party information to be withheld only when:

- the information falls within a specific class; and

- disclosure of the information could reasonably be expected to result in a specific injury, such as significant harm to a third party’s competitive or financial position, or result in similar information no longer being supplied voluntarily to the institution.

To maximize disclosure, the Commissioner also recommended that the Act explicitly state that institutions be required to release information when the third party to whom it relates consents.

In addition, she recommended that institutions not be allowed to apply section 20 to information about grants, loans and contributions third parties receive from the government, since Canadians have a right to know how this public money is spent.

This provision protects third-party business information, including trade secrets. The government collects third-party information through a number of avenues, such as during the grants, contributions or contracting process, as a part of regulatory compliance, or through public-private partnerships. The Supreme Court of Canada has noted that third-party information may often need to be protected, since it “may be valuable to competitors … and [disclosure] might even ultimately discourage research and innovation” (see Merck Frosst Canada Ltd. v Canada (Health), 2012 SCC 3 at para. 2). At the same time, dealings with private sector entities should be as transparent as possible for accountability reasons.

Institutions invoked this provision 5,300 times in 2013–2014. It was cited in nearly one quarter (24 percent) of the refusal complaints (146 files) the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015.

Proprietary information

A requester asked Public-Private Partnership Canada (PPP Canada) for records about its dealings with a company, Geo Group Inc., a provider of correctional, detention and community re-entry services. The institution refused access to some of the records, claiming section 20. During her investigation, the Commissioner learned that Geo Group had been asked for its position on disclosure by telephone only. Geo Group’s position at that time was that all the information in question was proprietary and that releasing it would damage the company’s ability to market its services.

The Commissioner questioned both PPP Canada’s use of section 20 and the process undertaken to consult Geo Group. Under section 27, an institution is required to advise a third party of its intention to disclose third-party records and provide a third party with an opportunity to make representations in writing. The third party is to be given 20 days to provide these representations.

As a result of the Commissioner’s investigation, an appropriate consultation was undertaken with Geo Group, after which PPP Canada decided that some of the information should, in fact, be released. (Geo Group Inc. had the opportunity to seek judicial review of this decision but did not do so.) The Commissioner then asked PPP Canada a second time to reconsider its position on continuing to withhold other information under section 20, which it did. In the end, the institution released all but a small amount of the withheld information to the requester.

Harm to commercial interests

In 2013 the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada published a paper on mobile telephone payments and consumer protection in Canada. In this paper, the authors referred to a study by the agency about the communications habits of new Canadians and urban Aboriginals. A requester asked for a copy of this study. In response to this request, the institution withheld 100 of 106 pages, citing section 20. The institution took the position, based on the representations of the third party that had prepared the study, Environics Analytics, that the exempted information was proprietary and that releasing it would harm its commercial interests. However, the Commissioner found through her investigation that the institution could not substantiate the expected harm. The Commissioner explained to the institution the criteria that needed to be met in order to apply section 20, after which the institution agreed to go back to the third party to reconsider its position. Subsequently, the institution released some additional information to the requester.

Bringing clarity to section 15

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended replacing the word “affairs” in section 15 with “negotiations” and “relations” to be clearer about what aspects of Canada’s international dealings would be harmed by releasing information.

Since institutions often rely on the classification status of historical information to justify non-disclosure under section 15, the Commissioner also recommended that the government be legally required to routinely declassify information to facilitate access.

Section 15 (International affairs)

This provision exempts information from disclosure which, if released, could reasonably be expected to injure the conduct of international affairs or the detection, prevention or suppression of subversive or hostile activities.

Institutions invoked section 15 more than 11,100 times in 2013–2014, an increase of 4 percent from 2012–2013. The provision was cited in 22 percent of refusal complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015 (135 files).

Conference contribution and budget figures

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner investigated a decision by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) to withhold under section 15 the amount it had contributed to a 2011 conference at Université Laval and the annual budget of its Academic Outreach program. In her investigation, the Commissioner found that CSIS had not provided sufficient evidence to show that releasing the information could reasonably be expected to injure efforts to detect, prevent or suppress subversive or hostile activities. Moreover, the Commissioner discovered that CSIS’s logo had appeared on the conference program, which was posted on the Internet, so its involvement in the event was publicly known. In light of the Commissioner’s investigation, CSIS agreed to release the amount of its contribution to the conference but not the Academic Outreach budget figures. The Commissioner continues to disagree with CSIS about withholding this information but the complainant did not provide consent for the Commissioner to file an application for judicial review.

Narrowing the application of section 23

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended that section 23 not apply to aggregate total amounts of legal fees.

She also recommended imposing a 12-year time limit on when institutions could withhold information under section 23 as it relates to legal advice privilege, starting from when the last administrative action was taken on the file.

Section 23 (Solicitor-client privilege)

This provision covers information subject to solicitor-client privilege.

Institutions invoked section 23 nearly 2,250 times in 2014–2015. The provision was cited in 20 percent of the refusal complaints the Commissioner registered in 2014–2015 (125 files).

Section 23 is a discretionary exemption that applies both to information privileged as legal advice and records that were created for the dominant purpose of contemplated, anticipated or existing litigation. While the latter privilege expires at the conclusion of litigation, legal advice privilege has no time limit. In some instances in the government context, there are public interest reasons to release information protected by solicitor-client privilege in order to ensure greater transparency and accountability. Consequently, when exercising their discretion to withhold information that is protected by solicitor-client privilege, institutions should consider all relevant factors, such as the age of the information, its subject matter and historical value.

Records of historical value

The issue of protecting historical records under section 23 arose during an investigation with Library and Archives Canada in 2014. The request had been for information that dated from the First World War and had to do with an application to the Supreme Court about why a soldier had been detained and sent to prison on charges of refusing to obey orders while on military service. The requester was confused as to why the institution had released personal records related to the soldier, but would not release those related to the government’s work to prepare for the soldier’s court hearing.

The requester complained to the Commissioner, who asked Library and Archives Canada to review the records. This resulted in its releasing one of four pages. The remaining pages at issue were a 1918 legal opinion from the Department of Justice. The legal opinion was on the meaning of the term “commitment” in what was then section 62 of a since-repealed version of the Supreme Court Act. The legal opinion referred to case law, some of which dated to the 1800s, as well as statutes such as the Lunacy Act and the Hospitals for the Insane Act of 1914. Both of these statutes were repealed decades ago.

The Commissioner found that the institution had properly determined that legal advice privilege applied to the legal opinion, but that it had not considered all the relevant factors for and against disclosure, including the age and historical significance of the information, when deciding to withhold it.

Throughout the investigation, the institution, on the advice of the Department of Justice Canada, refused to waive solicitor-client privilege on the records, despite their being nearly a century old.

At the conclusion of her investigation, the Commissioner formally recommended to the Minister of Canadian Heritage that the three pages be disclosed in light of the relevant factors that favoured disclosure. In response, the Minister referred the matter to the Librarian and Archivist for Canada, since he has delegated authority for access matters at the institution. The Librarian and Archivist responded that the three pages of records would be disclosed.

Section 23 and legal fees

The Commissioner is often asked to investigate complaints about institutions withholding billing information for legal counsel.

One such file involved Blue Water Bridge Canada, which had withheld in its entirety a two-page document comprising a cover letter and a statement of account from a legal firm. The Commissioner disagreed that solicitor-client privilege applied to these records. Upon consideration, the institution agreed with the Commissioner that the cover letter was not covered by solicitor-client privilege and released it to the requester. With respect to the statement of account, the Commissioner advised the institution that aggregate total amounts billed (such as appeared on the statement of account) tend to be neutral information and disclosing them does not reveal privileged information. Subsequently, the institution released these totals to the requester.

The Department of Justice Canada is frequently the subject of complaints about its decisions to withhold legal fee amounts. In two investigations the Commissioner closed in 2014–2015, the institution took the position that it could exempt this information under section 23 because it was related to ongoing litigation. In contrast, the Commissioner determined, based on case law, that releasing that information would not reveal any privileged information. The investigations resulted in more information, including the fee totals, being released to the requesters.

Other notable investigations

Limiting subsection 10(2)

To help curb the misuse of subsection 10(2), the Commissioner recommended in her special report on modernizing the Act that the provision be limited to several very specific purposes—for example, when releasing the information would injure a foreign state or organization’s willingness to provide Canada with information in confidence or when it would injure law enforcement activities or threaten the safety of individuals.

Neither confirming nor denying the existence of a record

Subsection 10(2) of the Act allows institutions, when they do not intend to disclose a record, to neither confirm nor deny whether the record even exists. When notifying a requester that they are invoking subsection 10(2), institutions must also indicate the exemptions on which they could reasonably refuse to release the record if it were to exist.

Since 2012–2013, the Commissioner has received 50 complaints about institutions’ use of subsection 10(2), with half of them coming in 2014–2015.

Subsection 10(2) was intended to address situations in which the mere confirmation of a record’s existence (or non-existence) would reveal information that could be protected under the Act. This could include, for example, the identity of CSIS targets or the activities of RCMP investigators.

However, the Commissioner’s investigations found several examples of institutions using subsection 10(2) inappropriately. For instance, the Department of Justice Canada cited the provision in response to a request for a letter from the Costa Rican foreign minister in which the minister asked for information from the institution, and the institution’s response. Through her investigation, the Commissioner learned that Costa Rican authorities had essentially publicly acknowledged that it had asked the Department of Justice Canada for the information in question. As a result, the institution ceased to rely on subsection 10(2) and released the records to the requester, albeit with many exemptions applied.

In another instance, DFATD cited subsection 10(2) in its response to a request for information about the visit of a Canadian consular official to an internment camp in Afghanistan. The Commissioner found through her investigation that the official did, in fact, visit the camp and that the institution’s public affairs group had released this information. In light of this, the institution reconsidered its position and released all the requested records to the requester.

Does dressing up in a costume threaten a person’s safety?

A request was made to the Canada Revenue Agency for copies of videos presented to CRA staff. CRA released a DVD containing a number of the requested video clips introducing various parts of the organization, but withheld one clip. The withheld clip showed various employees wearing Batman costumes and was protected under section 17. The requester complained to the Commissioner about the institution’s response.

Section 17 protects information when disclosure could reasonably be expected to threaten the safety of a person; it should not be used for the purpose of concealing embarrassing information. In light of the requirements of section 17, the Commissioner asked CRA to provide evidence of the harm that would result if the video clip were released. Initially, CRA maintained the application of section 17. After further requests from the Commissioner to show evidence of the harm, the institution eventually offered to allow the requester to view the clip on site, but the requester refused. CRA then proposed sending the requester the clip with the faces of the employees blurred. The requester agreed to this approach.

Costs associated with mailbox vandalism and graffiti

Canada Post Corporation (Canada Post) received a request for incidents reports of vandalism and graffiti to Canada Post mailboxes. The associated repairs and cleanup costs were also requested. In response, Canada Post withheld the information under paragraphs 18(a) and 18.1(1)(a). Section 18 protects the economic interests of government institutions, and paragraph 18.1(1)(a) is Canada Post’s unique exemption under the Act to protect its economic interest. The requester complained to the Commissioner and asked her to investigate Canada Post’s refusal to disclose the cost information.

Exemptions and exclusions added by the Federal Accountability Act

In 2006, the Act was extended to cover a number of Crown corporations, agents of Parliament, foundations and a series of other organizations as a part of the Federal Accountability Act. A number of institution-specific exemptions and exclusions, such as section 18.1, were also added to the Act at this time.

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended that a comprehensive review be undertaken of the institution-specific exemptions and exclusions added by the Federal Accountability Act to determine their necessity.

As a result of her investigation, the Commissioner determined that the institution had neither provided sufficient justification for the use of the exemptions nor properly exercised its discretion to release information. The Commissioner formally asked Canada Post to substantiate its position, at which point it withdrew its application of paragraph 18(a). It did provide arguments in favour of its continued exemption of information under paragraph 18.1(1)(a), but the Commissioner found them lacking. She wrote to the head of the institution and recommended that Canada Post release the specific cost information, which it did.

Duty to document decisions

The right of access relies on good record-keeping and information management, so that records are available for access. This right is denied when decisions taken by public officials are not recorded, particularly decisions that directly affect the public and involve the spending of public funds.

Documentary evidence

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner recommended establishing a comprehensive legal duty to document decisions within government, with sanctions for non-compliance. As a result, more information would be subject to the right of access. This would also facilitate better governance, ensure accountability and enhance the historical legacy of government decisions.

In 2014–2015, the Commissioner closed two investigations that determined that officials had not created records to document their decisions. The first investigation, at Transport Canada, revealed that the institution had taken no notes or minutes at some of the regular meetings officials had held with the City of Victoria, especially meetings related to the expansion of the harbour in 2010. The Commissioner asked the institution to do another search for records within various divisions and branches, and also to look for information discussed at regular meetings with the City of Victoria. Through these searches, Transport Canada located 10 pages and released them to the requester.

In the second investigation, into a complaint about a request for records regarding a decision to reduce the number of parking spaces in one part of the Experimental Farm in Ottawa, the Commissioner found that Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada staff had never created a record of their discussions and the arrangements for implementing this decision. All the records the institution released in response to the access request were from after the decision was taken. The Commissioner learned though her investigation that the decision to reduce the number of parking spots was made verbally and the work had been completed by employees of the Experimental Farm, resulting in minimal documentation. The Commissioner sought and received assurances from the institution that a complete search for records had been done and that any and all employees who might have been involved in the decision had been asked for records. Some additional records that were created after the requester submitted his request were found during subsequent searches. These were provided to the requester.

Systemic investigations

Delays stemming from consultations on records related to access requests

The Commissioner has long been concerned about the impact of inter-institution consultations on the timely processing of requests. Institutions carry out these consultations with other federal organizations, international governments and organizations, other levels of government and third parties about records related to access to information requests.

In 2010, the Commissioner launched a systemic investigation into the use, duration and volume of time extensions for consultations, especially ones that at the time were mandatory under the Act, and the delays to respond to access requests that may have resulted. The investigation focussed on nine common recipients of mandatory consultations under the Act: Canada Border Services Agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Correctional Service of Canada, Foreign Affairs and International Trade, the Department of Justice, National Defence, the Privy Council Office-Cabinet Confidences Counsel (PCO-CCC), Public Safety Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

During the investigation, a considerable amount of information was collected from the institutions by way of a questionnaire. The Commissioner commissioned a comparative analysis of international consultations (see box, “The challenges of consulting with foreign governments”). The Commissioner also sought and obtained representations from the nine institutions on their handling of both incoming and outgoing consultation requests.

The challenges of consulting with foreign governments

As part of the systemic investigation on consultations, the Commissioner commissioned a study on the treatment of consultation requests by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD) under sections 13, 15 and 16 of the Act.

At the time the study was prepared (2010), these consultations were mandatory. This meant that in most years, DFATD received more consultation requests than it did access requests.

The study’s author, Paul-André Comeau, found that in many instances DFATD had to consult with foreign governments in order to respond to consultation requests. This led to response times of up to 151 days for consultations and had a ripple effect on how quickly institutions could respond to the original access requests.

The report recommended several ways DFATD could streamline the process it followed at that time for consulting with foreign governments and organizations.

Now that consultations under sections 13, 15 and 16 are no longer mandatory—as a result of the Commissioner’s investigation—the number of consultation requests DFATD receives has dropped by 40 percent. The institution reported to the Commissioner in March 2015 that this fact, as well as specific measures it took in response to the systemic investigation, has meant that its average time to respond to a consultation request is now 58 days.

On the basis of the representations received and evidence gathered in the investigation, the Commissioner concluded that the mandatory consultation process impeded the ability of institutions to provide timely access to requesters under the Act. As a result, the Commissioner made recommendations to the Clerk of the Privy Council and the Minister of Foreign Affairs to resolve the matter and improve various practices related to consultations to these institutions (see table below). Both have accepted the recommendations.

During the investigation, significant changes were made by the government to two aspects of processing requests that were significant sources of delays: consultations on Cabinet confidences (see “Shedding light on decision making by Cabinet”) and consultations with respect to section 15 (International affairs) and section 16 (Law enforcement and investigations) of the Act. The Commissioner is still monitoring the effects of the changes to the Cabinet confidences process.

| Recommendations to the Clerk of the Privy Council | Recommendations to the Minister of Foreign Affairs |

|---|---|

1. That, where it is consulted under the new policy, PCO-CCC respond to such consultations within 30 days, the time within which institutions are generally required to respond to access requests. |

1. That DFATD strive to reduce the average time it takes to complete a consultation request, targeting the 30-day timeframe, mirroring the time period within which institutions are generally required to respond to access requests. |

2. That PCO-CCC ensure it is sufficiently staffed to handle the volume of consultation requests it continues to receive under the new policy. |

2. That DFATD continue its efforts to ensure that its access to information office is sufficiently staffed to handle the volume of both access requests and consultation requests received. In addition, that DFATD carry out awareness and training in program areas to emphasize that meeting access to information requirements is a legislative duty. |

3. That when it is consulted, PCO-CCC provide file-specific response times to institutions based on all relevant factors, including the number of pages and the subject matter involved. |

3. That DFATD cease providing to the access community its current average turnaround time for responses to consultation requests and instead provide individual guidance on receipt of each request, based on relevant factors, including the number of pages and the subject matter involved. |

4. That PCO-CCC take measures to ensure that there is sufficient training for institutions on the scope and application of section 69 of the Act so as to ensure consistency across government. |

4. That DFATD continue to pursue the possibility of sending consultation requests to foreign governments to those countries’ embassies or consulates in Ottawa, or develop an alternative solution to ensure that consultations with foreign governments are completed in a more efficient and timely manner. |

5. That PCO-CCC collect detailed data on the consultation process, statistical or otherwise, which it continues to receive under the new policy. |

5. That DFATD, with a view to making consultations with foreign governments more efficient, consider implementing elements of existing processes that allow Canadian institutions to consult directly with international organizations or pursue other options that would help ensure faster response times from foreign governments. |

6. That DFATD set fixed time frames for receiving responses to its consultations, and exercise its own authority under the Act to apply relevant exemptions and sever information when consulted institutions fail to respond within the time frames prescribed. |

|

7. That DFATD enable its case management system to track the full range of activities associated with both incoming and outgoing consultation requests. In addition, that DFATD carry out in-depth analysis of the information gathered in order to gauge and improve its performance with regard to consultation requests, and inform its decisions on workload allocation of resources. |

The Commissioner also made eight recommendations to the President of the Treasury Board in his capacity as the minister responsible for the proper functioning of the access to information system on measures that would improve practices related to consultations across the federal access to information system (see table below).

| Recommendations to the President of the Treasury Board | Response |

|---|---|

Clarify in the Directive on the Administration of the Access to Information Act that consulting institutions must fully and accurately respond to an access request when a response to a consultation request is not received from the consulted institution prior to the expiry of the extended due date. |

Did not agree |

Address the use of lengthy time extensions based solely on average response times by clarifying in the Access to Information Manual that, to be consistent with the statutory duty to assist and the directive, time extensions must take into consideration the volume and complexity of the information at issue. |

Agree |

Clarify in the manual that while appropriately established precedents may assist in establishing the length of extensions per paragraph 9(1)(b), it is a best practice to obtain an agreed-to response time from the consulted institution. |

Agree |

Issue guidance to institutions clarifying that closing files with outstanding consultation requests is not consistent with the Act, including the duty to assist. |

Agree |

Clarify in the manual that institutions consider and apply all exemptions and/or exclusions that they rely on to justify withholding information at the time they respond to the access request, to resolve the issue of institutions’ subsequently applying additional exemptions and exclusions during a complaint investigation. |

Did not agree |

Work closely with PCO and the Department of Justice Canada to ensure consistency in the application of section 69. |

Agree |

Amend the manual to provide guidance about the timelines for conducting third-party consultations set out in the Act, including advising that an extension per paragraph 9(1)(c) not exceed 60 days, given the statutory requirements of sections 27 and 28. |

Did not agree |

Clarify in the manual that when an institution does not receive a response from a third party within the statutory timeframe, the institution must issue a decision letter to the third party and make a subsequent release if no application for judicial review is initiated in accordance with the Act. |

Agree |

In April 2015, the Clerk confirmed progress on the implementation of the recommendations as they related to consultations for Cabinet confidences. She reported that the changes to the consultation process had substantially reduced the number of consultations with PCO-CCC. A significant improvement in response times was observed after PCO-CCC eliminated its backlog of consultations on Cabinet confidences in August 2014. For the remainder of 2014–2015, PCO-CCC completed 79.6 percent of its consultations within 30 days. PCO-CCC also undertook on-the-job training with seven departmental legal services units and two lawyers from Department of Justice Canada, which allowed for knowledge to be shared and contributed to further reduce the backlog.

Further consultation-related recommendations

In her special report on modernizing the Act, the Commissioner made other recommendations aimed at addressing problems associated with consultations:

- clarify that institutions may not take extensions to consult internally; and

- state that third parties that do not respond to a consultation request on time will be presumed to have consented to having their information released in response to an access request.

In April 2015, the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs also confirmed progress on the implementation of the recommendations. He confirmed that the changes to the Directive on the Administration of the Access to Information Act have had a significant positive impact on the consultations files at DFATD. The number of consultation requests has declined by 40 percent since 2011–2012. The institution has also improved its turnaround time from 2010 by almost 50 percent. Further, the institution is pursuing discussions with the United States and Australia on ways to improve state-to-state consultations.

In June 2015, TBS officials confirmed that changes had been made to the access to information manual to reflect the Commissioner’s recommendations.

Delays stemming from interference with processing access requests

The Commissioner closed a second systemic investigation in 2014–2015. This investigation, launched in 2010, looked into political or other interference with the processing of access requests and the delays to respond to access requests that may have resulted between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010. This investigation was launched as a result of evidence gathered from the institutions surveyed in the 2008–2009 report card process.

The investigation focussed on eight institutions: National Defence, Public Safety Canada, the Canadian International Development Agency (now Department of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Development), the Privy Council Office-ATIP, Health Canada, Canadian Heritage, Natural Resources Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency.

During the investigation, a considerable amount of information was collected from the institutions by way of a sampling of files and interviews with officials.

As part of the investigation, the Commissioner found evidence of delay caused by established delegation orders and resulting from protracted approval processes (see table below).

| Issues | Examples |

|---|---|

Interference |

|

Delays caused by non-delegated individuals |

|

Delays caused by delegated individuals |

|

Delegation of authority |

|

Delays due to the ATIP unit |

|

Other |

|

As a result of the investigation, most delegation orders of the reviewed institutions were amended to give full delegation to the access coordinator and/or to remove redundant levels of delegation.

This systemic investigation coincided with two individual investigations into allegations of interference at Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) (Part 1; and Part 2) in which the Commissioner made several recommendations to the institution to prevent political interference from recurring. She also encouraged all institutions and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to take note of the recommendations and implement them, as needed.

In light of the two PWGSC investigations, the measures implemented by the reviewed institutions in the course of the systemic investigation, turnover of staff within the reviewed institutions and the merger of CIDA with DFATD, the Commissioner decided that the most efficient way to conclude this systemic investigation was to make five recommendations to the President of the Treasury Board in his capacity as the minister responsible for the proper functioning of the access to information system (see box, “Recommendations following the Commissioner’s systemic investigation into interference with the processing of access requests”). The Commissioner also discontinued the systemic investigation against the eight institutions. The President of the Treasury Board did not address the Commissioner’s recommendations in his response, instead asking for information about specific instances of interference.

Recommendations following the Commissioner’s systemic investigation into interference with the processing of access requests

- That the Comptroller General undertake a horizontal audit to assess compliance with elements of the Policy on Access to Information that related to the treatment of requests.

- That TBS specifically include in its annual statistical report data related to high-profile subject matters and delays as a result of internal approvals.

- That TBS implement recommendations stemming from the Commissioner’s interference investigations at PWGSC:

- amend current policies and/or directives governing the processing of requests to set clear protocols for the interaction of departmental access officials and ministerial staff when processing requests;

- train access and ministerial staff specifically on the latter’s lack of delegation for, and limited role in, access matters;

- review the procedures institutions have in place for reporting instances of possible contraventions of section 67.1 of the Act (destruction of records) to ensure they are sufficient and that the guidelines establishing the procedures, as found in the Directive on the Administration of the Access to Information Act and the Access to Information Manual, have been considered;

- reinstate the mandatory requirement in the Directive that institutions have policy measures in place on reporting and investigating alleged breaches of section 67.1 to the head of the institution and to relevant law enforcement authorities;

- ensure that departmental and ministerial staff are trained on the policies established to report allegations of interference;

- require institutions to establish and communicate a process that will address requests by delegated authorities (access coordinators, deputy heads, heads, etc.) and/or non-delegated groups (communications, legal services, Minister’s office) for notification about impending disclosures;

- train departmental and ministerial staff members on the requirements of the duty to assist, including the obligation to respond to requests as soon as possible; and

- require institutions to inform the Commissioner about alleged obstruction under section 67.1.

- That TBS consider/study centralizing the access function for institutions.

- That TBS review the legislative changes related to sanctions found in the Commissioner’s special report on modernizing the Act and take steps to implement them by way of proposed legislative amendments.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

The Commissioner may launch a complaint under subsection 30(3) of the Access to Information Act.

- Footnote 2

-

See Interference with Access to Information, Part 2, p.37.